How to Manage the Innovation Butterfly

All actions have unintended consequences and risks. This so-called ‘butterfly effect’ requires specific strategies for innovators.

By Renee Hopkins

Does the flap of a butterfly’s wings in Brazil set off a tornado in Texas?

A 1972 research article asking that question brought the world a new metaphor to describe situations in which a seemingly tiny force sets into motion a cascade of events and grand outcomes that wouldn’t have happened without the initial flitter-flutter.

Most of the popular culture citations of the “butterfly effect,” though, missed the key takeaway: All actions have unintended consequences and risks. Because small imprecisions matter so much, the world is radically unpredictable.

Decades later, a pair of strategy wonks at the McCombs School of Business developed a theory that sheds new light on the butterfly effect’s implications for business.

McCombs Management Professor Edward Anderson and then-visiting professor Nitin Joglekar were deep into “a five-year conversation” on how companies trying to innovate can strike a path that rapidly diverges from the original route because of unpredictable, small changes.

“We said, ‘It sounds exactly like the butterfly effect. We wondered, ‘What’s creating these butterfly effects in the innovation world?’ From there, it’s not much of a step to coin the term ‘innovation butterfly.’” — Ed Anderson

Inspired by that conversation, Anderson and Joglekar (who is now teaching at Boston University and MIT) proceeded to write “The Innovation Butterfly: Managing Emergent Opportunities and Risks During Distributed Innovation.” The book frames management principles about innovation within the metaphor of the innovation butterfly, offering information on how managers can work with the butterfly effect rather than against it, and even use it to their advantage.

The prize for companies that learn to manage the innovation butterfly, says Anderson, is a chance at becoming another Apple Inc. — a continuous innovator capable of single-handedly shaping an entire market around its popular product offerings.

In contrast, many other companies “have one great nerve-shattering, market-shattering innovation, and then they can never go much beyond that. They’re one-hit wonders,” says Anderson.

And companies that fail to master the innovation butterfly risk becoming extinct in the face of new technologies, new markets, and new competitors. Just ask Kodak.

“If you can’t continually innovate, or you make innovations the customer just doesn’t care about, you’re going to forever be playing catch-up,” says Anderson. “Markets’ tastes move on to places you have no capability to handle.

Harnessing the Innovation Butterfly

Anderson teaches the ideas from his book in an innovation management class for the Master of Science in Technology Commercialization (MSTC) program at Texas McCombs. Joglekar teaches the ideas at MIT, in a class on innovation management and in various executive education courses.

Seventy-five percent of Anderson’s MSTC students are intrapreneurs (innovators within existing companies), and 25 percent are entrepreneurs trying to launch new startups. In either case, he says, “This isn’t going to be their last innovation project, so how do you build on it? How do you keep the momentum and move forward?”

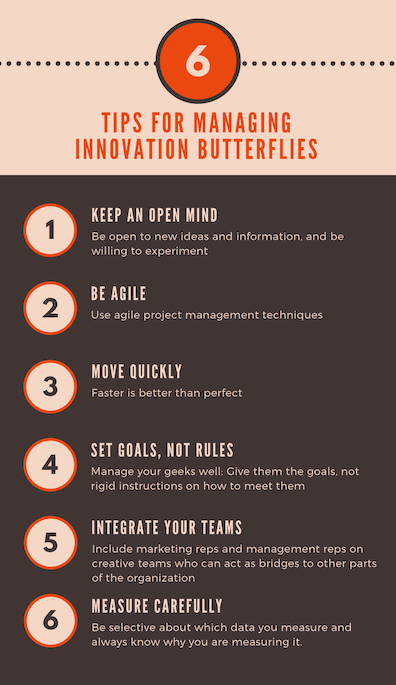

Anderson teaches his students the basic principles of managing innovation butterflies.

“The idea is to figure out what the effects of the innovation butterflies will be, so you can either work with it or get out of its way,” Anderson says.

Leadership Matters

In the book, Anderson and Joglekar write that the best way to dodge harmful innovation butterflies and harness helpful ones is through effective innovation leadership.

They contend that innovation requires leadership at many levels within a company — from the management of a single new product or service rollout to the management of a company’s entire innovation strategy and portfolio.

Decentralization is key, Anderson says. Companies with strict hierarchies and silos won’t succeed. At all levels, firms need an agile leadership strategy that is both reactive and proactive, he says.

Architect, Captain, or Coach?

The authors suggest three approaches for leading innovation: the leader as architect, the leader as ship’s captain, and the leader as coach.

Borrowing Peter Senge’s famous suggestion from his 1990 book, “Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of Learning Organization,” the authors make the case that the innovation leader’s work is more akin to being the architect of a ship than its captain.

Every innovation leader, regardless of his or her level in the organization, plays the role of an architect by exploiting capabilities and envisioning change.

The notion of continuous innovation is both a challenge and an opportunity for the leader-as-architect, says Anderson. “With continuous innovation, you can get some response, get an idea of where the butterfly is moving, if it’s moving along with you or if it isn’t — in which case you can change direction.

“If you plan innovation for years in the future, by the time the product comes out, the market will probably have gone somewhere you’re not going to match up with. ” — Ed Anderson

“Your odds of hitting anywhere near where the market wants to be are much lower than if you do it, say, two months out from now — because you have a pretty good idea of where the market’s going to be in two months. Two years? Who knows?”

So the leader-as-architect must spend considerable time designing the organizational structures that best support an agile, rapid innovation process that allows for experimentation and redirection.

A skilled innovation architect, says Anderson, also takes into consideration the company’s capabilities, who it hires, and the kinds of projects it selects. It’s also important to consider external innovation drivers, such as the government.

“A lot of what the government does ends up deriving an innovation butterfly, and sometimes not the one they expect. I doubt they anticipated that the 1972 emissions reduction and gasoline mileage requirements would bring on an electronics revolution in cars, which would then lead to anti-lock brakes and electronic suspension controls.”

Anderson teaches innovation leadership using historical examples, both real and imaginary. His preferred models: legendary explorer Captain Cook and his science-fiction alter ego, Captain Kirk.

Captain Cook, Anderson points out, was an expert at responding to the unexpected.

“The wrong thing or the right thing is either going to close down or open up possibilities as far as that expedition is concerned,” Anderson says. “He never knew what was going to happen. He was always trying to think ahead. He was really a scenario planner, thinking, ‘What am I going to do in this case or that case?’ He always had backup plans on backup plans.”

It’s crucial that the leader-as-captain be an expert at scenario planning, even in the face of unknowns, says Anderson. After all, while you’re adjusting to where the market is today, you’ve got to be planning for where it’s going or trying to create an entirely new market. And this, says Anderson, takes both scenario planning and luck.

“If you can hold all these different scenarios in your head and continually update them, some become more probable and some become less probable. Then you can be more creative, more quickly identify potential tracks for innovation, and also figure out the ones you want to avoid,” Anderson says.

Scenario planning must be rapid and continuous. “You do innovation better the faster you go, as long as you’re not spinning your wheels,” Anderson says.

“But that by itself isn’t enough. You need to continuously update your scenario planning as well. If you do one or the other, things will improve, but put them together and they’ll feed off each other. If you can get a little faster in your planning cycles, [and also] do more scenario plans, you’ll get much bigger bang for the buck than pushing on one or the other.”

But don’t let that pace squeeze out new tactics.

“Captain Cook was always willing to try new things, to experiment,” says Anderson. “Most experiments are going to fail. But even low-level managers should be willing to experiment. Sometimes you just have to take a risk.”

Like a successful sports team, an innovation-oriented firm needs a culture that nurtures maneuver-driven competition, while avoiding in-fighting, intra-team competitiveness, and ego-driven behavior.

The coach must scout or research potential recruits, assemble a team of players with key capabilities, develop strategies and tactics, empower the team, study opposing teams, and promote a winning attitude. And all of these elements must work together.

Also, the coach must manage unexpected disruptions such as injuries, incompetent officiating, and foul weather, as well as copycats and ever-changing defensive strategies that adjust to innovative offensives.

Meanwhile, in the business world, innovative managers must develop key technological capabilities by recruiting and retaining talented personnel. They must also design portfolios of product offerings that adjust to changing market conditions, as well as processes and tools to enable successful, timely project execution. Finally, the leader-as-coach must create a culture that values cooperation.

“One tip is that your technical people and engineers know more than you do. Your job is to channel them, don’t try to tell them what to do. They’re creative people.” — Ed Anderson

However, as anyone who’s ever managed an artist will tell you, it’s important to keep creative types’ eyes on the prize.

“Watch their goals like a hawk; otherwise they may create something wonderfully innovative that the market doesn’t want,” Anderson says.

Winning the Probability Game

Disruptive innovations — the kind that create new markets and take down established incumbents — come in various sizes and locations. “Some are easier to see than others,” says Anderson. “Some are just butterflies, and you might be able to harness those if you see them in the early stages.”

But some disruptions, he says, are like Craigslist, which seemingly came out of the blue and walloped the revenue stream of print newspapers. “Some of these disruptions are going to kill you. It’s just a probability game,” says Anderson.

“But if you pay more attention to your surroundings, plan better, decentralize — and you’re aware that you can harness the innovation butterfly and create your own disruption that will favor you — then you’ll do better.”

About this Post

Share: