Activism Moves Companies Beyond the Bottom Line

Businesses face increasing pressures — both internal and external — to address political and social issues, experts say

Corporations are taking stands in ways they never have before.

As issues from voting laws to policing to the Capitol insurrection receive attention, companies in Texas and across the nation are being asked to use their voices and dollars. We turned to our experts to understand what’s happening and why.

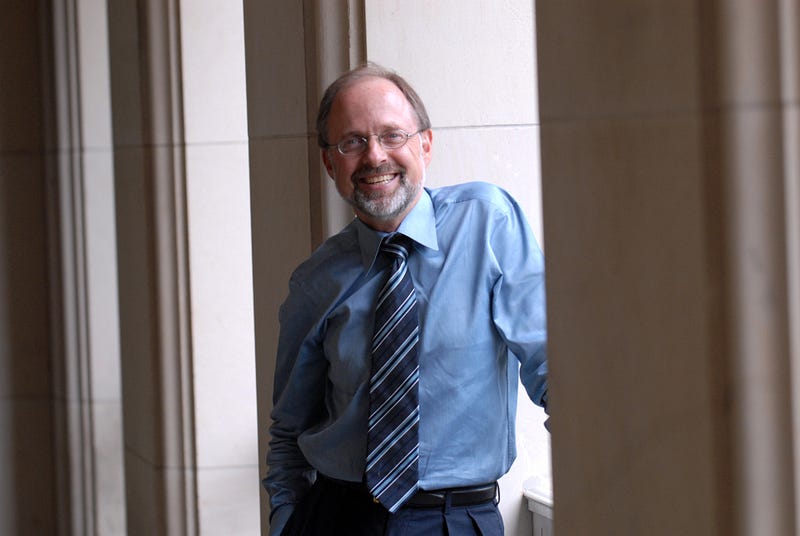

Robert Prentice, chair of the Department of Business, Government and Society at Texas McCombs who teaches business law and business ethics, and Tim Werner, associate BGS professor and an expert in corporate political activity, recently discussed the ways companies are taking the initiative — or being pressured — to speak up.

Prentice: Can you summarize the various forms of political speech happening today? How do business groups get their messages across and influence our democracy?

Werner: You have this weird mishmash of regulations on traditional political speech. Contributions are heavily regulated and expenditures less so, and that’s become truer over time. What we have emerging now, though, is this category of activist speech. Corporations aren’t really trying to affect an individual electoral outcome — whether a ballot measure or a race for office — but rather speaking out broadly on a political or social issue. That’s more akin to traditional exercise of freedom of speech. In some ways, it might be called “indirect lobbying” where the corporations aren’t directly lobbying policymakers, but instead trying to shape public opinion to then change officeholders’ views. A lot of this is done even when these issues aren’t active in the policymaking process.

We increasingly see it in — or aside — the policymaking process. It doesn’t fit our normal understanding of corporate political activity in a legal sense. A lot of these issues don’t feature either concentrated benefits or costs for the companies. That’s one of the classic definitions of corporate political activity: If we assume that corporations are self-interested rational actors, they’re only going to use their political resources to weigh in on fights that have an implication either on the benefit or cost side for them.

Prentice: Companies have been doing that increasingly these days. We’ve seen them weigh in on Black Lives Matter, the January 6 insurrection at the Capitol, and voter laws. It’s not about lowering tax rates. What do you think accounts for this shift?

Werner: A combination of both external and internal pressure. In terms of external pressure, recent social movements have been more successful than prior social movements in getting corporations to address these issues. Social movements have learned that asking the state to change policy is not always the best route. Corporations are actually often more open to it. The other part is that social movements are simply more successful because technology has facilitated the ease with which they can overcome collective action problems and mobilize large numbers of people to influence corporations.

The internal pressure is social movements inside companies. Folks who work in corporate communications and political activity will tell you that in the last 20 years, ERGs, or employee resource groups, have become much more active in pushing companies to change their policies. These are internal social movements that parallel ones you see outside of the company. You’ll see LGBT groups or affiliations around race and sex. There’s also just a general belief that younger generations — millennials and Gen Z — as employees, potential employees, and consumers are concerned about policies companies are adopting or not. Survey and experimental evidence shows they’re more likely to join or stay with a company if they agree with its social stances. Similarly, they’re more likely to buy from or remain loyal consumers if they agree with a company’s social stances.

Prentice: Through one of my daughters, I know a lot of young people who work in tech out in San Francisco. I’ve heard a million anecdotes about how much trouble those young employees give the C-suite executives over these issues. Does political activism both from outside and inside the company lead corporate executives to wish they didn’t have freedom of speech because it can raise such fraught issues for them?

Werner: If corporations could wash their hands of all of this, they would probably be happy. Historically, some U.S. states had regulations that only allowed companies free speech if the issue had ties to their business interests. So today, what we would think of as the most corrupt corporate activity was the one that people were actually OK with historically. It tried to limit companies talking about issues that didn’t relate to their bottom line in a material fashion. Those were some of the laws that were struck down and broadened political speech.

In the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s with the civil rights movement and then the ’90s with the gay rights movement, you saw more concrete demands being put on companies. They were asked to have affirmative action programs, domestic partner benefits. Those had, not huge, but more material implications for firms. Now, you’re seeing groups saying, “Take a stand on this social issue.” The material or tangible costs are lower, but those intangible costs — and the constant desire by activists for companies to be speaking out on every issue — is probably higher. I think there’s an attention cost that’s being borne by firms that they didn’t have in the past.

Prentice: Have companies been moved to take a stance based on moral considerations — equality, democracy, that sort of thing? Or is it all about the bottom line and the pressures they feel both externally and internally?

Werner: It’s tough for me to weigh in on that. First, because I don’t think corporations, as organizations, have a soul. We’re really talking about the C-suite individuals making the decisions and their motivations. There are certainly incidents where that’s clearly the case. Think about someone like Kenneth Frazier of Merck leaving the Trump administration’s CEO economic advisory councils in the wake of Charlottesville in 2017. Even in that case, which I would probably attribute to a moral stance, it didn’t stop him from joining that council in the first place.

The business leaders in Houston — and the coalition of companies more broadly speaking out against the Texas proposed legislation on voter integrity or suppression — didn’t call for the active repeal for legislation passed in 2011, which you could argue is when the Texas Legislature took the first and probably biggest steps in this regard. If companies want to be moral paragons leading the charge, they should not have just opposed the proposed legislation, but should actively lobby to repeal the 2011 legislation, which most notably changed voter ID requirements. Then, I would give them a lot more credit.

Prentice: Are there things that your research has uncovered about corporate political activity that we, as untrained lay public, would be surprised to know?

Werner: We concentrate a lot on the role of money on electoral politics, but for every dollar a corporation’s PAC gives, they commonly spend about $20 lobbying. Reforms for enhancing the integrity of our democracy should be targeted toward lobbying disclosure, and in particular drawing traceable connections between the company’s spending on lobbying and the individual lawmakers, regulators, or staff they’re meeting with. Because if we’re going to actually measure the influence of lobbying, we need to have data at that level. There’s maybe — if I’m being generous — 3,000 active corporate political action committees, and there are millions of corporations that could potentially have a PAC. You’re already starting off with a very low rate of participation, and PACs don’t give anywhere near the legal limit. So, they’ve either figured out a way to optimize this giving at very low levels, or they don’t think it’s worth much and do the bare minimum that’s required or expected of them.

I do think there is an expectation by policymakers that companies give. You saw that in the wake of the insurrection on January 6. Democrats were really upset at companies that suspended all of their giving as opposed to just suspending giving to Republicans or to folks who voted against certifying the Electoral College results. Democrats’ reaction is really illuminating. It shows a lot of this is not rent-seeking behavior by companies, but it’s actually rent extraction from the private sector by policymakers who need that money to run for office. That’s a story that’s not often told.

Prentice: It seems certain politicians are against corporate speech taking the form of campaign contributions, against the Citizens United decision, but are for corporate political activity when it takes today’s form. Whereas other politicians were all-in on political speech when it took the form of campaign contributions that went into their treasuries, but now want corporations to mind their own business when it comes to issues of political speech.

Werner: I wouldn’t call them hypocrites. I would just say their principle isn’t about speech. It’s about partisanship, and they’re fine with whatever form of speech supports their views. Neither side — the Republican side which bonds freer spending to elections, but not freer speech in this more activist sense, and the Democrats who want the activism, but not the spending in elections — holds consistent views. The Republicans have taken more of a hit simply because of Sen. Mitch McConnell’s threat of effectively unconstitutional bills of attainder against individual companies for speaking out and activism.

Prentice: Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas got a lot of pushback for his Wall Street Journal op-ed saying, “We Republicans have looked the other way when Coca-Cola didn’t pay back taxes and when Boeing asked for billions in corporate welfare. But we’re not going to do that anymore because you’re speaking out. And I’m not going to take any more political campaign contributions.” I was surprised at the numbers he gave: In his nine years in the Senate, he has only received — and this supports everything you’ve been telling us — $2.6 million in contributions from corporate PACs. So, it’s pretty easy for him to walk away from such a tiny amount. Does that make corporations wish they were giving more so that they’d have more leverage over Congress?

Werner: Companies probably would like a world in which they could give more, but go back to what was called “soft money.” They could give effectively unlimited amounts from the corporate treasury, but to parties. It was for “party building,” but basically for electoral activities. I think they liked that money was given to leadership who could then exercise some discipline. In general, that did tend to lead to moderation on both sides of the aisle, and consequently more favorable policy towards business. The 1990s was kind of the golden era of business-government relations, from the perspective of business. You had a relatively friendly Democratic Party and a very friendly Republican Party. The ways money can now flow into the political system has led to this much more contentious relationship between business in both political parties. Our system has really empowered ideologically extreme individual donors who can give directly to candidates or to third parties that make these independent expenditures.

Prentice: Looking at the big picture, what legal changes would you make to improve the situation — strengthen our democracy, reduce partisanship, et cetera?

Werner: Part would have to come from changes in regulation of money in politics. I tend to be a bigger fan of disclosure and reasonable — but hopefully still effective — limits on giving. Limits could be larger, especially for party organizations to fundraise money from individual donors. Disclosure could be much more accessible and detailed and better audited and enforced. Lobbying disclosure needs a wholesale overhaul with a lot more detail. One starting place is applying to domestically held companies the requirements we have on foreign corporations, in terms of the level of lobbying detail they have to report. That being said, there is a critique — especially in the legal world — that disclosure is a tool for well-educated, middle-class people to be better informed about politics. Those folks, if they want to, can learn a lot from enhanced disclosure, but most people do not have the time or skills to do so. I’m very sympathetic to that critique. But outside of money in politics, more structural change is needed.

Story by Jeremy M. Simon

About this Post

Share: