Protecting Your Retirement From Market Volatility

Your savings don’t have to bottom out even if the market does. McCombs investment experts explain how to safeguard your funds.

By Adrienne Dawson

A bad market can wipe out a lifetime’s savings.

That was the lesson investors learned during the Great Recession. Between 2007 and 2009, financial markets lost more than 30 percent of their value — causing American households to lose roughly $16 trillion in net worth. People ages 55–64 saw their wealth drop by more than 30 percent, and middle- aged Americans’ net worth decreased by more than half.

But some of the most exposed were those who had just retired: They’d left the workforce and begun withdrawing money from their retirement accounts, leaving their investments especially vulnerable to the sudden and sharp market downturn. For many, financial recovery was impossible. That’s the bad news. The good news is that there are ways to safeguard your retirement investments against market volatility.

McCombs Finance Professor Keith Brown and Empower Retirement Senior Vice President Van Harlow, M.B.A ’80, Ph.D. ’86, recently collaborated on research that looks at retirement account performance under varying market conditions and investment strategies that can keep retirement accounts safe even if the market goes south.

WHAT IS THE BIGGEST THREAT TO A PERSON’S RETIREMENT SAVINGS?

“We tend to think about longevity and inflation risk as the biggest risks retirees face, but sequence-of-returns risk is the biggest by orders of magnitude,” says Harlow.

Sequence risk refers to the order of negative or positive returns your investments earn starting at the time you retire and begin withdrawing money from your account. In other words, if the market soars as you enter retirement, you’ll earn good returns on a large balance, and your funds will last much longer than if the market nosedives — as it did in 2008 — just as you leave the workforce, ushering in your retirement years with a depleted base.

WON’T THE POSITIVE AND NEGATIVE RETURNS AVERAGE OUT OVER TIME?

No, because the combination of withdrawing funds while simultaneously losing money to negative returns in the early years of retirement means the total value of the account can’t rebound, even after the market does.

If you retire into a bad market, as many people did during the Great Recession, “you can deplete your retirement savings very quickly,” says Harlow.

BUT HOW CAN YOU PREDICT WHAT THE MARKET WILL DO?

You can’t, so it’s wise to use financial vehicles that can protect your funds no matter what.

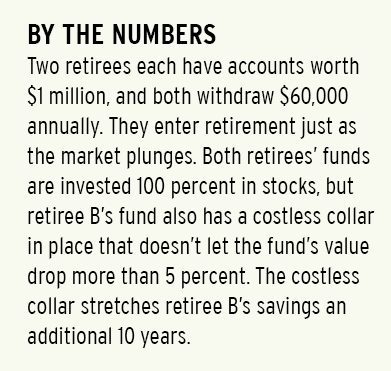

One of them, known as the costless collar option strategy, ensures that an account holds its value if there’s a sudden market downturn. “It’s like an insurance policy for an investment fund,” explains Brown.

Here’s how it works: A costless collar is made up of a put option and a call option, which give the investor the right to sell or buy stock at a certain strike price. Together, they provide a floor and a ceiling beyond which the value of a fund can neither rise nor fall. It’s called “costless” because the investor accepts limits on profits by selling a call option (which caps how much you can earn) in order to pay for the expensive put.

A put option is the key. Once exercised, the value of the investor’s fund can’t drop any lower. For those who retired at the start of the Great Recession, for example, having a collar in place would have prevented the value of their retirement fund from free-falling.

HOW DOES THIS WORK FOR THE AVERAGE INVESTOR?

While buying derivatives to protect your investments is possible, it’s also difficult. “You’re going to be hard-pressed to find many financial advisors with the expertise to do that,” says Harlow.

An easier route is to invest in mutual funds that have a collar built in. Absolute return funds use hedging strategies like collars to protect investments from market volatility.

DOESN’T ASSET ALLOCATION DO THE SAME THING?

Conservative asset allocation can keep an investor from being over-exposed to stocks, but that means the investor’s rewards are very limited when the equity market does well.

On the other hand, a collar offers a firm floor that guarantees a fund’s value won’t sink beyond a certain point, while allowing for a higher exposure to stocks. Gains are capped, but they aren’t eliminated.

WHAT IS THE BEST ASSET ALLOCATION FOR THOSE CLOSE TO RETIREMENT?

Conventional wisdom says aim for a 60/40 equity/fixed income ratio, but Brown, an advisor to the board of trustees of the Teacher Retirement System of Texas, says it’s a rule that’s been misinterpreted. “That allocation benchmark is meant for institutional investors, like TRS, with long time horizons, not for individuals whose time horizon until retirement decreases daily,” he explains.

“From age 25 to 40, you need a high percentage of equity — 80 to 95 percent,” says Harlow. “Then every year after 40, start rolling that down gradually to land at a conservative equity allocation by your selected retirement date.” Harlow and Brown’s research finds that for most retirees, the optimal equity allocation should actually be closer to 10 percent than 60 — if a person’s main goal is to protect their savings once those funds become their primary source of money.

So, if you’re looking to keep your retirement savings safe, both the 90/10 (fixed income/equity) asset allocation strategy and the costless collar are worth considering.

WHAT ELSE SHOULD INVESTORS KEEP IN MIND?

McCombs Finance Professor Clemens Sialm, who studies retirees’ investment behaviors, says individuals need to take more responsibility for understanding and overseeing their accounts. “It’s important to be informed and learn as much as you can,” he says.

Watch out for fees: Every fund comes with a fee, and those expenses eat away at a fund’s profit, says Sialm. Expenses vary greatly depending on the type and amount invested — from a few basis points to several percentage points of the assets invested. Sialm says that doesn’t mean investors should always go with the cheapest fund, but make sure the performance justifies the cost.

Think about your health: The healthier you are, the more you’ll need to save to pay for additional years of Medicare premiums and routine care co-payments. For example, in a recent study, Harlow and Brown find that a 65-year-old woman in good health will incur about $45,000 more in medical costs over time than someone with Type II diabetes.

Save, then save more: The exact percentage you should save depends on your goals, age, and constraints, but Sialm and Harlow agree that a good goal is to aim for 10 percent of your gross salary, and Harlow adds that someone who makes $250,000 will need to save even more if they want to maintain their standard of living in retirement. “You can’t invest your way out of a problem,” Harlow insists. “You have to save for it.”

Originally published at www.texasenterprise.utexas.edu on June 20, 2017.

About this Post

Share: