Mapping a Manager’s Brain on Incentives

How do incentives affect a person’s decisions? Researchers give managers an fMRI to find out.

By Steve Brooks

Can restructuring a manager’s pay help that manager make better business decisions and fewer expensive mistakes? A tool from neuroscience — functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) — opens a window to peek into the brain and find out.

Brian White, assistant accounting professor at the McCombs School of Business, studies both numbers and the ways executives and investors use them to make decisions. He researches psychological theories to explain why human beings don’t always make the rational decisions that classical economics expects of them.

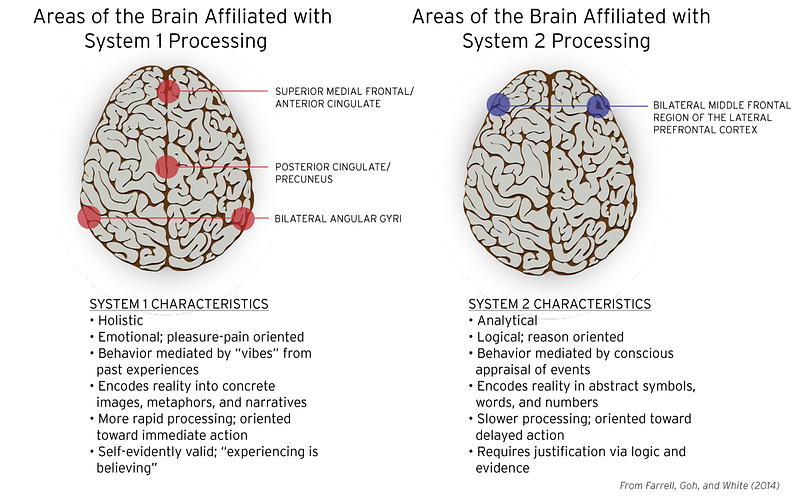

Specifically, he studies a theory that distinguishes two types of cognitive processing: System 1 processing is dominated by affective or emotional reactions, while System 2 processing balances those with rational economic considerations. Previous studies have documented how System 1-based decisions can turn into costly business mistakes, so White wondered how a business could encourage more logical, System 2-type thinking.

That led him inside the skull. With Anne Farrell, associate accounting professor at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, and Joshua Goh of National Taiwan University, White zeroed-in on performance-based incentives — compensation arrangements that tie bonuses to financial results. With the use of an fMRI machine, they could map specific regions of the brain to see exactly what causes rational (System 2) thinking.

Before going into the machine, their subjects, 27 graduate business students, read profiles of fictional colleagues. Some were designed to rile their emotions, like an arrogant manager named “Ken.” Says White, “We had people, prior to going into the scanner, saying, ‘I really hate Ken. He’s such a jerk.’”

Once inside the scanner, the subjects were told they would earn a fixed wage of $25 for making rapid-fire choices among 90 investment proposals. The screens included profit projections for each proposal. They also included photos of the executives sponsoring the proposals: some with positive emotional associations, others with neutral or negative ones. The students had eight seconds to choose, the optimal time for the machine to measure increased blood flow to particular parts of the brain.

After a short break, subjects looked at the same proposals again. This time, they were told they would get bonuses based on profits from four of the projects. Which four, they didn’t know, but it was an incentive to pay closer economic attention to all the projects.

The result, the researchers found, was that the two rounds lit up different areas of the brain. The first round stimulated System 1 (affective) regions like the superior medial frontal/anterior cingulate. The second round activated most of these System 1 areas as well, but added System 2 (rational) regions like the bilateral middle frontal region of the lateral prefrontal cortex.

Choices also differed between the two rounds. When offered a performance-based incentive instead of a fixed wage, the subjects were 24.9 percent more likely to choose the economically better investment.

White concludes that performance-based incentives fostered a more balanced mode of thinking in his subjects. Emotions still influenced decisions but were tempered with objective economic considerations. He notes, “Performance-based incentives seem to work when they’re needed most, when emotional reactions are likely to be costly.”

The prospect of a bonus can spur more deliberate thinking, says White, but bonuses can also be expensive. He’s interested in finding other kinds of incentives that might stimulate System 2 thinking at a lower cost.

An example is commitment-based devices, in which someone makes a commitment and then feels obligated to keep it. He’s done pilot research in which subjects went into negotiations with explicit lists of the key criteria to use in making decisions. Those lists, he found, seemed to change the ways they processed information during the negotiations.

“It does suggest we may be able to find other methods for changing cognitive processing,” says White. “Performance-based incentives are costly, so to the extent we can find other ways to improve decision-making, understanding the mechanism is essential.”

The Study

The Effect of Performance-Based Incentive Contracts on System 1 and System 2 Processing in Affective Decision Contexts: fMRI and Behavioral Evidence is published in Accounting Review. This article was originally featured on Texas Enterprise on February 17, 2015.

Originally published at www.texasenterprise.utexas.edu.

About this Post

Share: