How to be a Creative Genius

It may seem like an elusive thing, reserved for the likes of Picasso or even Elon Musk. But each of us is capable of churning out creativity. Consider this your guide to great ideas.

By Tracy Mueller

It’s 3:14 p.m. on a Thursday in September. Your phone’s weather app tells you it’s an unimaginable 105 degrees outside, and yet you feel frozen solid by your building’s AC. It seems like half the world — or at least your co-workers — are out on vacation, surely having the time of their lives in scenic Cape Cod or Lake Tahoe or at least Port Aransas. Their kids are probably even perfectly well behaved, getting along and playing quietly together at this very moment.

And here you sit at your desk, deadline looming. It’s a big project, and one that you actually care about. You’ve been given the necessary resources, and you have the knowledge and skills to complete your task. And the deadline is, indeed, looming. You just need to take a deep breath, focus on what you need to do and get to wor … Oh look at that, an email forward with the subject line “Cute kittens LOL.” You don’t see that just every day. Better look into this.

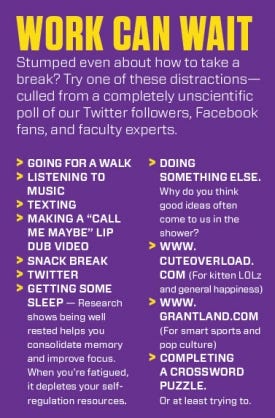

Sound familiar? Even the most passionate employee gets in a rut at work on occasion. So how can you get out of it? And is it possible to train yourself to be more creative? We’ve got expert advice, plus a list of distractions that might actually make you more productive.

Getting Unstuck

“When you get stuck, it’s because you are unable to remember what you need to know to solve the problem,” says Art Markman, professor of psychology and author of the book “Smart Thinking.” He also co-teaches the class “Maximizing Mental Agility to Improve Creativity” as part of Texas Executive Education’s new Innovation Certificate.

Markman argues that when you’re stuck on a problem, there are really only three possibilities:

1. No one on the planet can solve the problem.

2. Someone knows the answer, but it’s not you.

3. You do know something that will help you, but you haven’t retrieved that knowledge yet. You’re asking your brain the wrong question.

Photography by Matthew Mahon

Illustrations by Ronald Kurniawan

If that’s true, “You have to change your description of the problem so that your brain can recall different information,” Markman says.

The first step is to determine the “inner essence” of your problem. What problem are you really trying to solve? Ask yourself, “If I wrote a book about my problem, what would I call it? How would I describe the problem in three words to someone else?” Those simple exercises can help you clear out the clutter to focus on the heart of the problem, Markman says.

Imagine you’re trying to create a better toothbrush. Instead of getting stuck obsessing over bristles, reframe your challenge: the goal of a toothbrush is to remove film from a surface that you don’t want to damage.

Now that your core problem has been identified, move beyond thinking about it on a superficial level, and turn to analogies or the abstract. With the toothbrush example, what are other problems that face a similar challenge? Examining how people clean house siding or restore old paintings might offer some unexpected inspiration for dental care.

It’s also important not to self-censor too much at this point in the process, or focus on only producing great ideas.

In a pair of studies, accounting professors Steven Kachelmeier and Michael Williamson considered the effect of paying individuals for either the quantity or both the quantity and creativity of their ideas. What they found offers an important lesson: People who were paid for creativity were no more creative — and were much less productive — than people paid merely for quantity. They worked hard to develop creative ideas, but the results weren’t there.

In other words, it’s difficult to motivate for creativity. Williamson’s advice is to keep producing ideas and trust that the creativity will follow.

“When we try too hard to be creative, we tend to be overly critical of our ideas and get stuck,” he says.” When that happens, it is important to just put your ideas out there or write them down. The only way to ensure no creative ideas is to not generate any ideas.”

Kachelmeier likens the potentially crippling focus on trying to be creative to a type of stage fright.

“The harder you try the harder it is. Just relax, have fun, do the work, and some of it will be quite good,” he says.

How to Cultivate Creativity

A lot can get in the way of thinking creatively. Social conventions, a pressure to perform. Even past success.

“Sometimes the barriers we face are from our past solutions,” says Gaylen Paulson, associate dean and director of Texas Executive Education. In other words, when we experience success with one approach, we return to that well with each new challenge. But that is a stagnant strategy that overlooks how the problem may be different, and it might prevent a new, better idea from developing.

He adds that sometimes — in an attempt at efficiency — our brains actually get in the way of creativity.

“Our brain is really good at seeing patterns and organizing things into manageable chunks. It does it automatically. But sometimes that restricts our solutions.” — Gaylen Paulson

So how can we guide our brains toward more imaginative problem solving?

Paulson offers these tips on how to be a creative thinker:

1. Be curious. Kids are natural explorers and questioners, but that tendency is often discouraged as we move into adulthood. (After all, the adage doesn’t warn that curiosity mildly injured the cat.) But research shows our minds need to be stimulated in new ways in order to stay sharp. Travel. Take a class. Ask questions. Otherwise you risk developing “cognitive arthritis,” where thinking becomes rigid and it’s more difficult to learn new things.

Photography by Matthew Mahon

Illustrations by Ronald Kurniawan

2. Search for the unusual and surprising. Ideas are about being new and different. Take inspiration from the unexpected. As Oscar Wilde said, “Consistency is the last refuge of the unimaginative.”

3. Set optimistic goals and pursue them. People with aspirations tend to achieve more. If you have mediocre hopes, you’ll get the job done, but you will miss out on other opportunities. Don’t settle for the “pretty good path.”

4. Create an environment for yourself that works. This could be your physical environment or time of day. The point is, know yourself and what works for you. If desk clutter or multitasking knocks you off track, remove it from your workspace.

5. Allow for time off-tasks when thoughts and ideas can ferment. Relax while accomplishing something. Garden, do a puzzle, or mow the lawn. Patterned behavior keeps your brain working while focusing on something other than your problem.

6. Develop a specialty, but keep your eyes open. You need a certain amount of expertise in order to work in any field, but it’s easy for your thinking to become congested in your own domain. Innovation often occurs when ideas from two separate realms are combined together. For example, the person who developed Pringles’ space-saving stacked chip was inspired by the idea of pressing tree leaves into uniform shapes in between book pages.

7. Be complex. When negotiating, if you’re battling over just one thing — money, for instance — you’re unlikely to reach a creative conclusion. But introducing multiple variables into the equation — ownership stake, timeline, office space — opens up more resources and gives you more latitude. Additionally the creative process can feel contradictory at times. Think intensely about a problem, then don’t think about it at all. Be an expert, but explore something you know nothing about. Learn to be comfortable with that.

If all that sounds like a lot of work, you’re not alone.

“We crave certainty,” Paulson says. “Too much uncertainty when it’s not your choosing is cognitively effortful,” so we often slip back into routine to feel comfortable. But of course remaining the same isn’t a sustainable business model.

“If you do it the same way as last week, somebody’s going to pass you up,” Paulson says. “Saying, ‘Hey, we did the same as last year,’ isn’t anything to celebrate.”

If you struggle with change, Paulson suggests thinking about it in terms of what you could lose if you don’t. The fear of loss is a greater motivator than hope for gain.

And sometimes it’s simply a matter of acknowledging that creativity can be tough.

“Creative problem-solving situations are likely to make you uncomfortable,” Markman says. “And mental discomfort is usually a sign that we’re doing something incorrect. So what we have to realize in the context of creative problem solving is that the whole situation may make you uncomfortable, and that’s OK.”

— Additional reporting by Jeremy Simon

Originally published at www.today.mccombs.utexas.edu.

About this Post

Share: