Creative Workers Need Both Incentives and Breaks

For best results, churn out ideas, rest, repeat.

Based on the research of Steve Kachelmeier

To encourage good ideas from employees, companies can’t simply demand creativity on the spot. Instead, they need to spur workers’ creative activity — and then wait.

“You need to have the incentives to get a lot of creative ideas. The kicker is that it doesn’t happen right away,” says Steve Kachelmeier, the Randal B. McDonald Chair in Accounting at Texas McCombs.

Incentivizing creativity has been one of the accounting professor’s research interests for more than a decade. An initial study showed that paying for the production of more ideas resulted in more ideas, but did not actually improve creativity, while another study found workers who chose to be paid for their creativity failed to come up with better ideas.

What does seem to work, according to the latest research, is unfettered idea generation combined with “incubation.” When, after making an effort to crank out as many ideas as possible, a person has time to relax, their most creative insights often arise. It’s the phenomenon of struggling with a problem while at your desk, only to have inspiration strike when you’re taking a shower, driving to work, or otherwise not focused on the project. “Even when you’re doing something else, your subconscious mind works in the background. Then, all of a sudden, you may get this epiphany,” Kachelmeier says. “It happens to all of us.”

Prime the Pump, then Wait

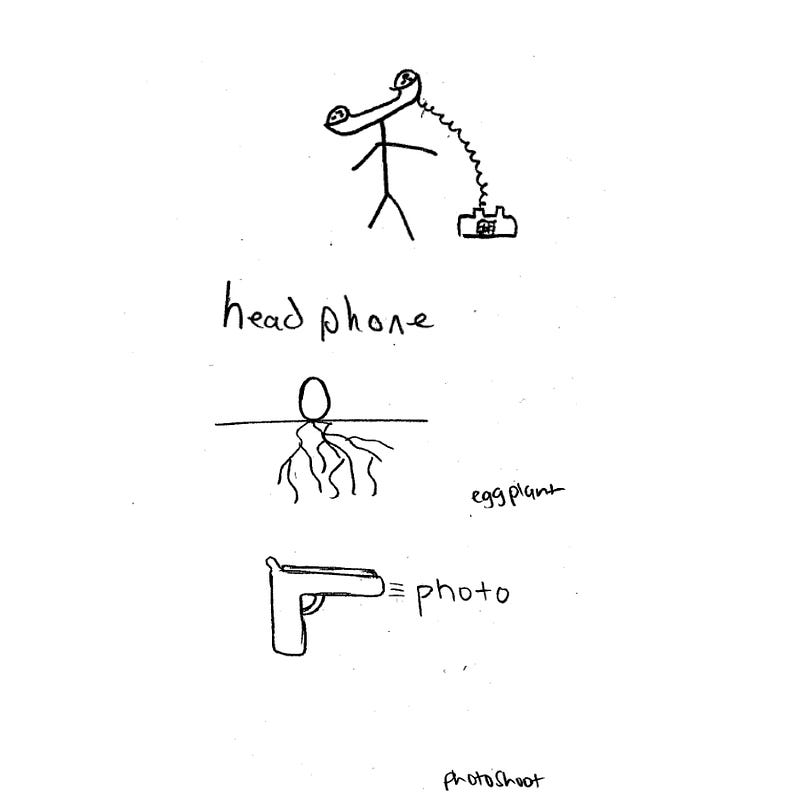

In a pair of recent studies, Kachelmeier and researchers from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Assistant Professor Laura Wang, BBA/MPA ’05, Ph.D. ’14, and Professor Michael Williamson, gave participants a creative task. Students were asked to create rebus puzzles, the sort of riddles where words, phrases, or sayings are represented using a combination of images and letters.

For the study’s first phase, the researchers paid participants for a variety of outcomes: the number of ideas they generated, regardless of creative quality; high-creativity ideas; ideas that were above a minimum threshold of creativity; or a fixed-wage of $25, regardless of what they came up with.

The results? No group was more creative than the fixed-wage students. For example, the minimum creativity threshold group generated significantly fewer high‑creativity ideas. And while the pay-for-quantity group produced more rebus puzzles, their ideas were no better, according to the independent team of graders who later reviewed their rebus puzzles for creative quality.

Ten days later, all the participants returned to collect their money. When they arrived, the researchers had a proposition: Jot down any additional rebus puzzles that came to mind and earn an extra $10.

“As you might imagine, a lot of students just said, ‘Okay, thanks for the $10, buddy. Here’s a stupid idea, I’m out of here,’” says Kachelmeier. “But some of them actually sat down and wrote some really good stuff.” Students who were originally paid for quantity “definitely had a distinct creativity advantage,” says Kachelmeier, producing both more and better ideas.

After the study’s initial phase, it’s unlikely coming up with more rebus puzzles was on their to-do lists. Or so it seems. “Maybe in their subconscious, they’re coming up with the ideas they wished they had 10 days earlier,” says Kachelmeier.

So why did they do so well? It seems related to their earlier efforts to try different approaches.

“Priming the pump leads to more creative ideas.” — Steve Kachelmeier

Give Them a (Short) Break

For the next stage of their study, the researchers paid half the participants a fixed amount and half for the number of ideas they produced. While the pay-for-quantity participants produced a lot more puzzles, they once again didn’t generate better ideas than the fixed-pay group.

Next, researchers changed their environment entirely. Participants were led outside on a quiet 20-minute walk through the University of Illinois campus.

When the students returned to the lab, they were asked to create additional puzzles. Just like in the 10-day study, following their break, those originally paid for quantity once again produced much better puzzles.

“You need to rest, take a break, and detach yourself — even if that detachment is 20 minutes.” — Steve Kachelmeier

Not Forcing, But Setting the Stage

Some companies are already recognizing the benefits of formalizing employee downtime. The Harvard Business Review describes global aviation strategy firm SimpliFlying, which required members of its approximately 10-person staff to each take a scheduled week’s vacation every seven weeks. When asked to rate employees before and after their mandatory time off, managers noted a 33 percent increase in creativity (alongside smaller gains in happiness and productivity).

According to the researchers, employers can’t demand creativity from workers, through pay or pressure. But neither can companies simply let workers do whatever they choose all day, such as playing ping-pong or relaxing in beanbag chairs, and expect good ideas. The researchers outline a different proposition: Get employees to work hard at generating ideas, uncritically reward them for producing a large number of ideas, provide downtime, and then have them try again.

“The recipe for creativity is try — and get frustrated because it’s not going to happen,” says Kachelmeier. “Relax, sit back, and then it happens.”

With increasing automation and outsourcing eliminating many jobs, Kachelmeier says what’s left is companies’ need for workers who bring judgment, creativity, and innovation to their roles. “We’re paying people to think,” he says. “We’ve got to figure out how to do that effectively and what role incentives play. That’s where we’re playing our own small part.”

“Incentivizing the Creative Process: From Initial Quantity to Eventual Creativity” was published in the March 2019 issue of The Accounting Review.

Story by Jeremy M. Simon

About this Post

Share: