Clinical Optimization

Researchers work together to help patients see multiple clinicians on one visit

By Steve Brooks

When a first-time patient walks into the Musculoskeletal Institute at Dell Medical School’s new UT Health Austin clinical practice, they might be surprised by one feature: an empty lobby. If they’ve filled out their electronic paperwork ahead of time, they should be whisked straight into an exam room.

That’s by design, says the institute’s medical director Dr. Karl Koenig. When he was setting up the clinic, which opened in October 2017, one of his mantras was, “A doctor’s office should keep the appointment time you set.”

Koenig is fulfilling that pledge, thanks to a collaboration with Texas McCombs and UT Austin’s Cockrell School of Engineering. Professors in all three schools are applying concepts from supply chains — like how to get oilfield equipment to a drilling site at the right time — to help patients see health care providers.

“Our challenge is how to coordinate a network of providers around a patient,” says Douglas Morrice, Bobbie and Coulter R. Sublett Centennial Professor of Business at McCombs. “We’ve designed it so that someone can see several different clinicians on one visit.”

It’s the kind of interdisciplinary problem the Value Institute for Health and Care was created to solve, as a joint project of the medical school and Texas McCombs, says Managing Director Scott Wallace.

“Health care is decades behind the rest of the economy in how it applies business concepts,” Wallace says. “We need the operations expertise of people like Doug to show us how to allocate resources. We want providers to deliver as much care as is feasible, but we can’t have six people sitting around waiting for one patient.”

Navigating Patient Flow

Re-engineering health care delivery has interested Morrice for a long time. In 2012, the University of Texas Health Sciences Center at San Antonio asked him and Cockrell Professor Jonathan Bard to analyze its anesthesiology clinic. Patients faced long waits to prepare for outpatient surgery, while doctors were delayed by missing information.

Morrice and Bard, working with the medical center’s Dr. Susan Noorily, came up with the idea of a new position: a nurse navigator, who helps patients gather all their information before their appointment. With that change, the clinic was able to see 19 percent more patients the following year.

Next, the medical center asked the researchers to tackle a tougher challenge: a unified scheduling system for two clinics. When patients saw an anesthesiologist, they often turned out to have other conditions needing treatment. How could they get into an internal medicine clinic the same day, instead of waiting weeks?

“We wanted a system that could accommodate unscheduled patients,” says Dr. Luci Leykum, chief of the division of general and hospital medicine for the medical center. “And we wanted to make it work without everybody staying late and paying overtime.”

Uncertainty Principles

To handle the math, Morrice called on Kumar Muthuraman, McCombs professor of Information, Risk, and Operations Management. His specialty is decision-making under uncertainty in areas like financial markets and energy trading.

At a medical clinic, Muthuraman says, uncertainties abound, from which patients will miss appointments to which ones will need a second doctor. Make it two clinics, and risks for havoc grow exponentially. “If one person gets delayed seeing a doctor, it cascades through the system,” he says.

He devised algorithms to juggle three goals: keep patients from waiting, keep doctors from sitting idle, and avoid overtime. Each time someone requests an appointment, a computer tries fitting them into several open slots. Then it calculates which slot will produce the optimal outcome, a single number that balances the three objectives.

Delivering Value

When Koenig, the director of Dell Med’s Musculoskeletal Institute, met Morrice at a McCombs Health Care Symposium, he says, “It was a ser- endipitous connection.”

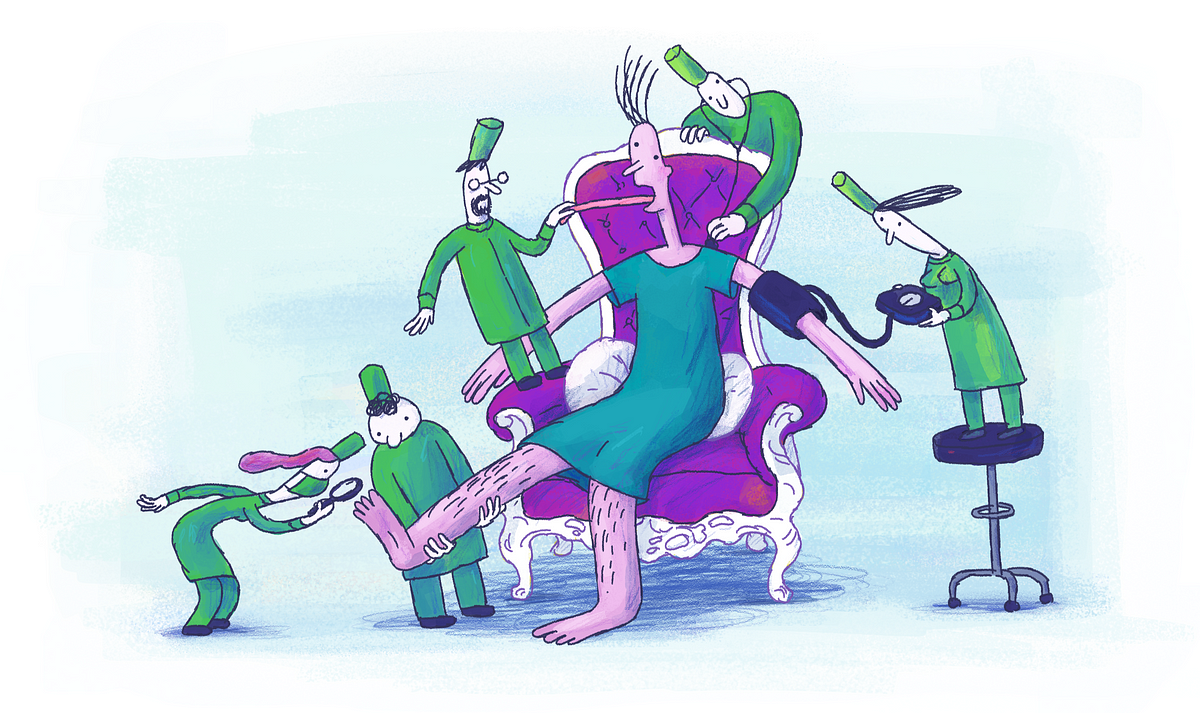

Koenig was busy setting up a new kind of clinic. Instead of bouncing a patient from one health care practitioner to another, it would bring different types of providers to the patient. They would work as a team, called an integrated prac- tice unit. If a patient needed to see multiple team members, they would each sequentially come to the patient, all in a single appointment, with the patient staying in the same examination room the whole time.

But to make that vision work, the clinic would have to minimize waiting time, for both patients and providers. Morrice might provide the missing link.

At Koenig’s request, Morrice and Bard modeled the clinic-to-be, complete with numbers of rooms and mixes of cases. Provider time slots were scheduled at five- and 15-minute intervals.

“You spread patients more efficiently, so that they don’t overwhelm the clinic at the end of the day,” Morrice says. The system updates provider availability as the day goes along.

New Horizons for Research and Care

When his clinic for hip and leg pain opened in October 2017, Koenig expected it to accommodate 28 patients a day. Today, thanks to the system’s efficiency, it is handling 37.

Even though more patients are being served, Koenig never has to rush, because the schedule adjusts, depending on which providers on the team each patient ends up needing to see. “I have the amount of time I need to spend with each person,” Koenig says. “I don’t have to cut it short to see four people who turn out not to need surgery.”

He’s now using Morrice and Bard’s system at the Musculoskeletal Institute’s three other clinics: for arm pain, back and neck pain, and sports injuries. A variation is being tried in operating rooms at the school’s teaching hospital, Dell Seton Medical Center at The University of Texas. While patients benefit, so does Texas McCombs, says Wallace. “Innovations happen at the intersection of disciplines. This fusion of different disciplines creates tremendous opportunities for faculty to explore whole new areas of research.”

Morrice is already taking his model a step further. He’s working on adding telemedicine to the mix.

“We can fill in white space in schedules by interlacing telemedicine appointments,” he says. “They’re generally follow-up patients. They might only need to check symptoms or make sure they’re using the right medicine.”

For Koenig, though, the system’s biggest reward is that he can watch human beings instead of clocks. “Patients can feel the difference,” he says. “I’ve had people weep because they felt that for the first time, providers were really paying attention to them.”

New Clinical Model Serves Patient Needs Instead of Doctors’

Four years, ago, an Austin resident had to wait an average of 400 days to see an orthopedic surgeon at the city’s public hospital. Now, at UT Health Austin’s Musculoskeletal Institute, the wait is one week.

Medical Director Dr. Karl Koenig gives credit to a pioneering care model called an integrated practice unit. It fits the school’s core principle of value-based care: making patients healthier at lower cost, by organizing services around their needs rather than doctors’.

An IPU assembles a diverse team under one roof, able to address all a patient’s issues in the same visit. For hip and knee pain, Koenig’s team includes a surgeon, an associate provider (nurse practitioner, physician’s assistant, or chiropractor), a medical assistant, and a physical therapist. It shares a social worker and a registered dietician with other IPUs at the institute. After a patient enters the clinic and is roomed, the appropriate providers sequentially address the patient’s conditions. Most often, patients are first seen by an associate provider who determines what additional treatment is required. Then, other members of the team are called in, depending on what best serves the patient at that point in their condition.

“A patient comes in with joint pain,” explains Scott Wallace, managing director of the school’s Value Institute for Health and Care. “Surgery may be one solution, but they may have a condition better treated with physical or behavioral therapy. We’re trying to look at what’s really wrong and what’s going to help them the most.”

Because clients get comprehensive care in one stop, there are fewer follow-ups and more slots for new patients. They enjoy better outcomes, too. Dell Medical’s early hip and knee surgery patients went home a day earlier than those not treated by an IPU, and 65 percent reported improvement by their next visits.

“Designing and Scheduling a Multi-disciplinary Integrated Practice Unit for Patient-Centered Care” by Douglas J. Morrice, Jonathan F. Bard, and Karl M. Koenig, is forthcoming in Health Systems.

About this Post

Share: