Avoiding Catastrophe: A New Way Retailers Can Stock for Hurricanes

McCombs professors have developed a better way to get supplies to customers before the next storm strikes.

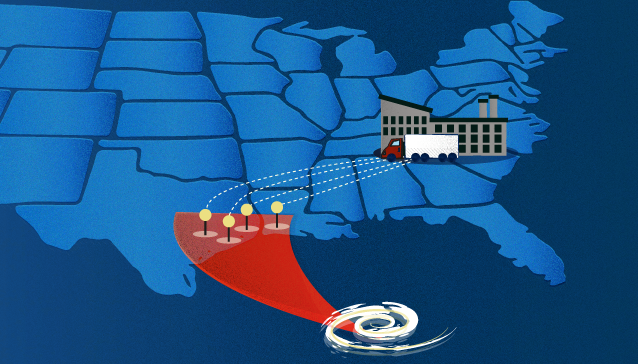

For retailers with locations along the Gulf and Atlantic coasts, figuring out how to send supplies to stores that might be in the path of a U.S.-bound hurricane is a challenge. It may seem straightforward, but according to McCombs IROM Professor Doug Morrice, it’s anything but.

“The trick for the retailer is to get the right quantity to the right location at the right time,” he says, “but storms come with a lot of uncertainty.”

Together with McCombs Associate Professor John Butler, doctoral student Paul Cronin, and Fehmi Tanrisever from Bilkent University in Ankara, Turkey, the researchers partnered with a prominent Gulf Coast retailer that was looking to improve its storm planning processes. During past hurricanes, the retailer hadn’t always gotten supplies where they needed to be. “That’s what drove us to start working with them, to make things better,” Morrice explains.

They’ve developed an inventory system that compares three key pieces of data in a way that’s never been done before:

- Store-specific sales trends from past hurricanes

- Storm simulations from the National Weather Service

- Retailers’ operational and logistical constraints.

It’s a model that gives retailers a real-time assessment so they have enough time to get critical supplies where they need to be.

“Now You’ve Got a Problem”

Retailers have generally used one of two methods to move inventory before a hurricane: They either send everything they have to the stores they believe would be most affected as soon as the initial landfall projections come in, or they split their inventory into two equal shipments when the storm is five and three days from shore.

Both methods have snags, he says.

“If you send everything to an area, and the storm changes direction, now you’ve got a problem, right? You’ve sent all of your inventory to the wrong place.”

Getting it back and moving it might not be feasible, and it will certainly be costly. On the other hand, the half-now, half-later option gave the retailer the ability to monitor the storm’s path, but it still didn’t take consumer demand into consideration.

By tracking five years’ worth of sales data surrounding 15 hurricanes for each of the Texas retailer’s Gulf Coast locations, the researchers were able to uncover consumer buying trends unique to different regions of the state.

One of the first things they discovered was that people buy certain storm supply products in predictable patterns, but those patterns vary by location. In other words, when a hurricane is approaching the Gulf, shoppers in Galveston might stock up right away, while residents in Corpus Christi might wait until the storm is closer to land. What’s more, Morrice and his team could see what types of supplies people in different cities gravitated to — be it water, batteries, or canned goods.

“Because we’re able to correlate data on the status of the storm with the buying demand we saw in the past, we can give the retailer specific information so they can say, ‘Okay, this is what’s happening. Now we know what to expect,’” Morrice explains.

He adds that it’s as much about preserving a retailer’s reputation and goodwill by ensuring supplies are available when shoppers are ready to buy them as avoiding a potential crisis.

When to Pull the Trigger?

Morrice describes the scene inside a retailer’s headquarters right before a hurricane as a “war room” where inventory is pushed out to the stores in a centralized fashion. Supplies are moved out quickly, but there is a lot of room for error, in part because the storm’s path can change quickly. “This adds a layer of uncertainty for the retailer,” the researchers write.

By evaluating both the storm’s current trajectory and buyers’ shopping patterns during past hurricanes, the researchers’ model minimizes the guesswork for the retailer. For instance, they found that if shoppers themselves feel uncertain about a storm’s path because the projected landfall cone encompasses two regions, they’re more likely to stock up on supplies right away. In that case, it’s actually better for the retailer to send all supplies to those to regions in one early shipment. However, if a storm is heading toward one region only at the five-day forecast, the model can advise how much inventory to send out in two phases, in case the path shifts suddenly when the storm is three days from landfall — the last possible time a retailer can safely redirect inventory.

Just as important, their model accounts for retailer constraints, such as distribution center inventory levels and anticipated transportation costs. It then weighs those constraints against the potential for a supply shortage. “We find that even with higher costs, most scenarios call for sending supplies out in two shipments, and the model helps estimate that cost up front,” says Morrice. “Better information means retailers know when to pull the trigger.”

Surprisingly, perhaps, the researchers found that a hurricane’s intensity doesn’t drive consumer behavior: they prepare the same way for any size storm. “They’re looking at that cone projection to find out where it’s going to hit. And so even after all the data mining and technical analyses like strike probabilities, we found that the sales data were highly correlated to forecasts from, of all things, The Weather Channel,” Morrice says with a laugh. “And of course, the retailer is watching The Weather Channel’s forecasts, too. That was the piece of the puzzle that really blew this open.”

Supporting Hurricane Inventory Management Decisions with Consumer Demand Estimates is published in the Journal of Operations Management.

Published at www.texasenterprise.utexas.edu on May 17, 2017.

About this Post

Share: