The Origins of AI

The hidden figures of artificial intelligence, as explained by Associate Professor James Scott, co-author of a new book tracing the history of the ideas that power AI

By Jeremy M. Simon

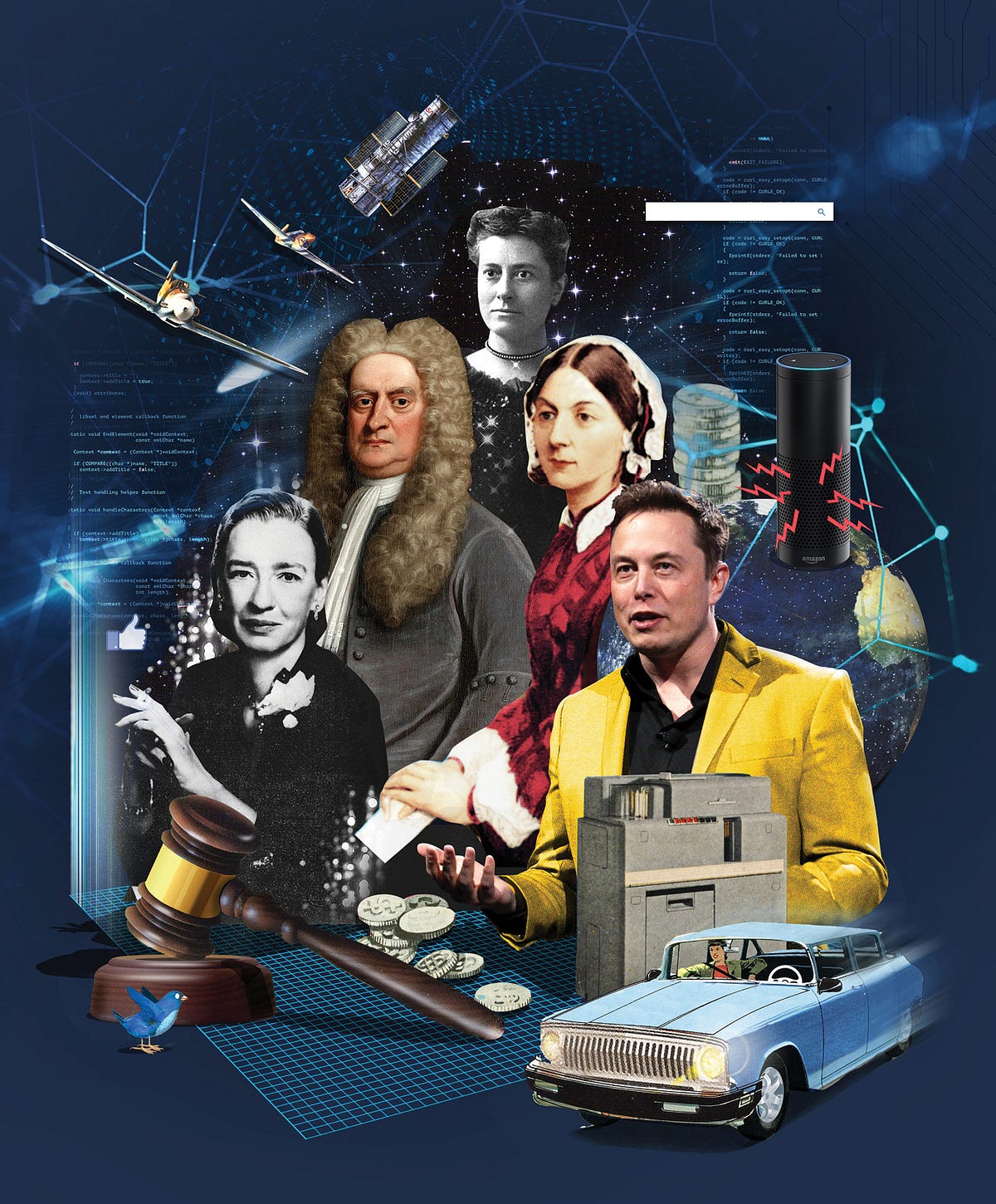

The ideas behind artificial intelligence have been around for a long time, according to James Scott, associate professor of Information, Risk, and Operations Management at McCombs, and the co-author of “AIQ: How People and Machines are Smarter Together.” People like Sir Isaac Newton, Florence Nightingale, and Admiral Grace Hopper are just a few of those whose breakthroughs paved the way for the AI systems that power so many of the products and services we enjoy today, from Alexa to Siri to Netflix. Yet prominent naysayers — Tesla’s Elon Musk, for example — warn that artificial intelligence is bound to bring about a Terminator-like dystopian end of the world as we know it. Scott says such fears are unwarranted, and that he doesn’t know a single reputable AI scientist who thinks that kind of thing is a realistic possibility on any timeline for the foreseeable future.

Scott recently discussed these and many other issues surrounding today’s AI explosion.

Why is AI taking off now?

The answer is technology, the speed of computers. It’s impossible to convey intuitively how fast computers have gotten at computing numbers.

We like to use a car analogy. If we go back to 1951, the fastest computer around was called the UNIVAC. It was the size of a room, based on vacuum tubes, and could do 2,000 calculations per second, which is radically faster than any human being. The fastest car was the Alfa Romeo 6C, which can travel about 110 miles per hour. Today, both cars and computers have gotten faster. Formula One cars travel over 200 miles an hour and computers are radically faster than the UNIVAC. But if cars’ speeds had increased as much as computers, the modern Alfa Romeo would travel at 8 million times the speed of light.

If you do a Google image search for a picture of an African elephant, the mathematical models at the heart of that require 1.5 billion little operations of additions, multiplications, and subtractions of pixel values in order to classify one image. That was the model maybe four or five years ago, so it’s probably even more today. When you think about the complexity of that set of mathematical operations, it’s a good thing the modern graphics card in a decent gaming laptop can do 1.5 billion calculations in about .00001 seconds. That’s why it’s important to have fast computers.

Aside from computing speed, what else explains AI’s sudden rise?

The scale of data sets. If you digitized the Library of Congress, you’d get about 10 terabytes worth of data. That is 120,000 times less data than was collected by the big four tech firms — Apple, Google, Amazon, and Facebook — in 2013 alone. That’s a lifetime ago in internet use, and the pace of data accumulation is just accelerating at incredible speed. Today, if you want to classify an image, think about one megapixel image. One megapixel is one million pixels. Each pixel has a red, green, and blue value; that’s three million numbers. If you want to fit equations where every single example in your dataset has three million numbers, these are going to be really, really, really complicated equations. The basic rule in statistics is that the more complicated an equation you want to fit to your data, the more data you need. So it’s a good thing we have 120,000 times as much data as the Library of Congress rolling onto our servers every year to be capable of making really accurate predictions about the world.

How old are the ideas behind AI?

In the 17th century, Isaac Newton used fundamentally the same mathematical tools that our computers have today, as did Florence Nightingale in the 19th century. It’s the same set of ideas, with the modern addition of the incredible computing power at our disposal.

Your book tells the stories of AI discoveries made centuries ago. Are there any historical heroes who never got the recognition they deserved?

Henrietta Leavitt made an absolutely fundamental discovery in astronomy: She fit an equation to data she compiled from the old great telescopes back in the 1900s and 1910s. The equation allowed astronomers to measure distance. That’s a surprisingly hard problem in astronomy. You look up in the sky and see a flickering light. You don’t know whether that star is bright and far away — and only seems dim because of how far away it is — or if it’s really close and dim, like Venus.

The equation she gave us in a really beautiful three-page paper published in an astronomy journal set the stage for an incredible revolution in human understanding. It wasn’t until about 10 years later that we started to see the fruits of that in astronomy. The person who made the most spectacular use of Leavitt’s discovery was Edwin Hubble, the first person to discover that ours is not the only galaxy in the universe. He got all of the applause, with politicians knocking on his door and Einstein coming to have a glass of wine at his house in California.

Henrietta Leavitt was forgotten for a couple of reasons. One, she was a woman, and at that time the chauvinism of astronomy meant she couldn’t even publish a paper alone. She had to have a male sponsor. Second, unfortunately, she died of cancer several years before Hubble made his discovery. For me that’s a bittersweet story, the notion that this very unheralded woman who made a fundamental discovery in astronomy never got to see the fruits of her labor and the recognition that she deserved in her lifetime — or even today.

How is Leavitt’s work being applied to AI?

She was using the fundamental principle that the big tech firms use to fit equations to their data and build the kinds of systems that allow Facebook to identify friends in photos, Google to make accurate predictions about what ads you’re going to click, or Amazon to decide what goods they should ship to which warehouses to anticipate demand. It’s that fundamental idea of fitting an equation to data that she took off the shelf and applied. That’s the key thing that drives the modern digital economy. I don’t know a better story than Henrietta Leavitt’s to explain how fundamental that is to the process of discovery.

Why did you decide to write the book?

Nick Polson, my co-author, and I are both teachers. This book is primarily a way to answer all of the great questions our students had about AI. They would learn about probability in class and recognize the applicability of some ideas to the modern AI space and want to know things like how self-driving cars work or Netflix makes better predictions about what movies we’re going to watch.

From there it really bloomed into something more than we ever expected. In writing and researching the book, we realized there was a fundamental breakdown in the narratives about AI that you encounter in the media or talk about at the lunch table among colleagues.

On the one hand, you have this huge amount of hype coming from the business world. Companies are making it seem AI is going to fix every problem for humanity. But then on the other side, you have the Elon Musks of the world, AI doomsayers who say AI is going to kill everything that we care about: jobs, privacy, or something we haven’t even thought of yet. As educators, we believe that to participate in these important debates, you really have to understand what AI is, where it came from, and how it works.

Are there legitimate AI worries?

There are judges who do criminal sentencing in Broward County, Florida, using machine learning algorithms to help guide their decisions: Somebody’s been convicted of a crime, and the judge decides how long a sentence they should receive.

You input a set of features about that defendant. Maybe it’s their criminal history or the severity of the crime. On the basis of those features, the algorithm makes a prediction about how likely that person is to commit a crime in the future. It classifies defendants as either high-risk or low-risk for recidivism, and using that risk prediction the judges informed their sentencing decisions appropriately.

When does it become problematic?

What if that algorithm uses features that predict the probability somebody’s going to be incarcerated for a crime, but are totally unfair? The obvious example would be the race of the defendant: If you look at U.S. incarceration rates stratified by race, it’s about half a percent for people of white descent, and it’s about 2.5 percent for people of African descent. That reflects centuries of racial discrimination and brutality in this country.

Now, if being black predicts higher rates of incarceration, any machine learning algorithm worth its salt will find proxies for dark skin. And that is totally wrong. There’s no way we would allow that in a human who was explicit about it, and we absolutely shouldn’t allow it when a machine does it. These algorithms are not allowed to know explicitly, for example, what race somebody is, but they are all allowed access to things that are very strong proxies for those. For example, your family’s history of incarceration is a very strong proxy for race in the criminal justice system in America. There’s a worry that these algorithms are simply reinventing proxies for race.

So what’s the result?

In Broward County, if you look at the algorithms’ track record, it’s much more likely to predict that a white person is at a low-risk of recidivism, when in reality that person commits a crime again. For black defendants, it’s much more likely to wrongly classify somebody as high-risk when in reality they don’t go on to commit another crime.

There’s no other word for that than racism. It’s really important that we don’t treat these algorithms like a microwave oven, where you just punch in set of numbers and walk away. You really have to have humans who know what they’re doing — who understand the algorithms, their potential downsides, and legal standards of fairness — using these to maybe supplement a decision, not make them.

What else should we be concerned about?

As a consumer, I want all digital firms to respect that my data should never be used against me, in ways that I didn’t consent to. That has to be a bedrock principle of the digital age. At the same time, you also have to recognize the positive externality associated with pooling and sharing data. Health care is an example. I personally view organ donation as a moral issue. We shouldn’t compel people to donate their kidneys, but it’s an issue of personal morality. I’m on the organ donor registry so somebody else’s life can go on after mine is over.

To me, data is the same. We don’t let hospitals hoard your kidneys when you die. Why should we let them hoard the data about your kidneys? If the data about my kidneys can be used to save someone else’s life, I should share that, too, in a way that privacy can be respected and individual medical information can’t be traced back or used against me. But there are technological solutions to that.

There are the moral issues of Facebook abusing your data and health care data needing to be made private. But if our data can help make people’s lives better, longer, healthier, and happier, we should be sharing. We can better humanity.

Historic Innovators Paving the Way for AI

Rear Admiral Grace Hopper, a computer science pioneer, invented a methodology that revolutionized computing. Her “compiler” idea in the 1950s led to the widespread use of computer programming languages. Hopper’s innovation enabled the spread of digital technology into every part of life, and eventually enabled us to speak our commands to Alexa.

Astronomer Henrietta Leavitt published findings in 1912 that were used to measure the distance of pulsating stars over millions of lightyears. Her prediction rule is now used in AI-based pattern recognition systems, including Facebook image recognition and Google Translate.

Sir Isaac Newton, the greatest mathematician of his time, became warden of England’s Royal Mint in 1696 and was tasked with increasing production and reducing the variability in weights of silver coins. Yet, he failed to detect a simple error in the averaging system the mint used to detect weight anomalies. Figuring out how to average lots of measurements properly is one of data science’s most important ideas. It shows up today in a huge range of AI applications from fraud prevention to smart policing.

Florence Nightingale became a living symbol of compassion for treating injured British soldiers in the Crimean War in the 1850s. It’s less well-known that she was also a skilled data scientist who convinced hospitals to improve care through use of statistics, setting the precedent for today’s international system of disease classification. Today, Nightingale’s legacy is seen in promising AI healthcare applications on the horizon, from laser-guided robotic surgery to algorithmic vital sign monitoring to personalized cancer therapies.

Hungarian-American statistician Abraham Wald fled the Nazis in 1938, and joined Columbia University’s Statistical Research Group, where he created a “survivability recommender system” for aircraft during WWII. His algorithm discovered areas of aircraft vulnerability based on analysis of only those planes that were recovered after attack. Netflix uses a similar approach in its recommendation system (but for unwatched films rather than shot-down planes) when likewise faced with missing data.

About this Post

Share: