Poised for the Future

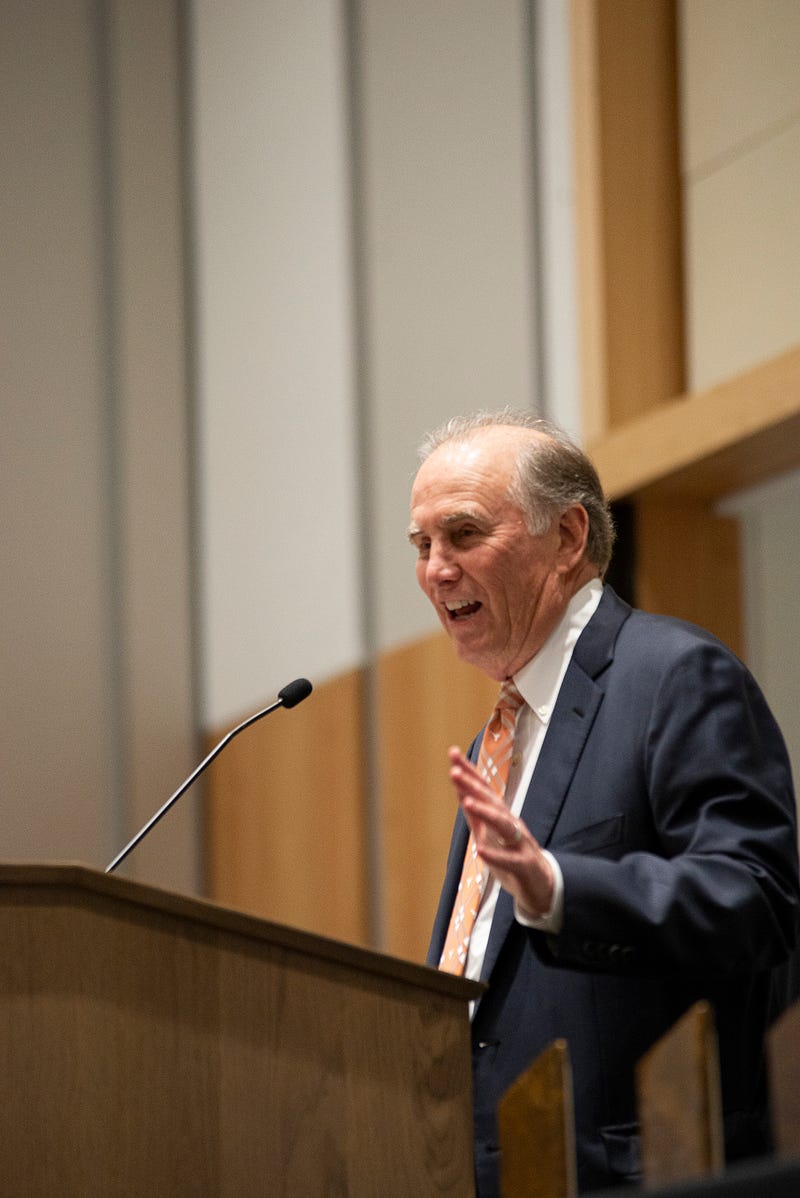

Ray Nixon, BA ’74, MBA ’77, reflects on the perseverance of the American market — and the importance of equipping young leaders to impact and serve society.

Tonight we’re here to celebrate 25 years of the MBA Investment Fund. Thanks to its creation, UT MBA students have been uniquely exposed to the ups and downs of the capital markets and to the psychology and fundamental tenets of investing.

It’s a good time for us to take a step back together to reflect, especially given how much anxiety there seems to be about the future. We’re living in a time of immense uncertainty. There are trade wars, investigations, and predictions of environmental calamity on the horizon. Tensions at home and abroad are uncomfortably high. Questions about our national identity loom, as it appears capitalism itself will be on trial in the upcoming election. Technology is rapidly advancing beyond what we can imagine — and although we largely feel it will be for society’s betterment, we also know it will come with many unintended consequences. It’s normal to wonder, “How will our country and economy fare in the coming years with all the challenges that appear poised to confront it?”

When there is a great deal of uncertainty about the future, it’s not a bad idea to look back at history for insight and direction.

That’s what I’ve had the opportunity to do the past several weeks while preparing for this event. I’ve been thinking back on what we’ve been through in the markets and world since this MBA investment fund began, and I’ve been reminded of just how extraordinary a journey it’s been. I’ve also been reminded of some of the things that helped us navigate it successfully, bringing us where we are today.

Over the next few minutes, I’d like to recount historical parts of the last 25 years with you. I hope it will boost your confidence for dealing with the road ahead — confidence that we will continue to adapt, innovate, and succeed no matter what is in store.

1994 was a special year of creativity. An impressive number of things we still enjoy today first showed up. Movies like Forrest Gump, The Lion King, and The Shawshank Redemption were just coming out. A little-known sitcom called Friends was just gaining fans. The internet was in its infancy. Netscape was just getting off the ground, while somewhere in Seattle a guy named Jeff was in his garage building a site called Amazon.

Take a moment to recall where you were.

I was just beginning my career on the buy side after working 15 years on the sell side for two great businessmen, Sandy Weill and Jamie Dimon. Priest Holmes was entering his junior season at running back for Texas, while across campus, Dean George Gau and Dr. Keith Brown were working to get the MBA fund started. None us knew what lay ahead, but ’94 would turn out to be the baseline start of an extraordinary run for the stock market and economy. Greenspan was about to raise interest rates for the last time. And with one last hike of rates in ’95, the economy showed just how ready it was to advance.

Over the next five years, amazing activity occurred in the equity markets. We witnessed “Bank Heaven,” as investors called it, watching the four big banks we know today — JPMorgan, Wells Fargo, Citi, and Bank of America — arrive at their current statuses through an incredible 35 separate deals. We witnessed the unprecedented valuation explosion of Cisco, which, having gone public in ’90, grew to $500 billion by ’99–making it the largest market capitalization company in the world. That same year we also witnessed the introduction of the euro, as investors across the world became excited about a sudden new market with a combined consumer population that surpassed American consumption power.

It was in the U.S., however, that the most significant developments occurred. Netscape’s IPO introduced the country to the World Wide Web and a place called the Silicon Valley. Everything seemed to be advancing at a faster pace. The Wall Street Journal observed that what had taken General Dynamics 43 years to achieve — becoming a corporation with a $2.7 billion market capitalization — seemed to have only taken Netscape about one minute in comparison. Only five years later, AOL paid $10 billion to acquire them entirely.

But not everyone fared well through this period. Long Term Capital also began in ’94. It was the premier hedge fund of its day from first launch. With something of a dream team at the helm with John Merriweather, Robert Merton, and Nobel Prize-winning economist Myron Scholes, the fund started with $2.5 billion in assets. Over the next three years it became massive, performing well-enough to reach $126 billion in assets. But built as it was on an imprudent amount of debt, it found itself too leveraged to survive a Black Swan (an event beyond the normal range of volatility). When the Russian devaluation occurred in ’98, long-term capital became short term, collapsing under the pressure of its extreme debt — a valuable reminder of how leverage can shorten your time horizon.

’94 to ’99 was undoubtedly a boom. But booms are predictably followed by busts, and the dotcom bust in 2000 led to a painful decline in the markets. What we could not have predicted then was the number of serious crises that awaited us over the next two decades, the first of which was just around the corner.

On 9/11 we experienced the first attack on American soil since Pearl Harbor. The U.S. markets opened at 8:30 a.m. as usual, but by 9:03 the second plane had hit and the whole world was changed. It was a literal and symbolic assault on our economy and the world markets. Seven years later, another painful and frightening shock occurred when The Great Financial Crisis unfolded. It was the most severe economic decline our country had faced since The Great Depression. And there were of course many other, smaller, but significant disasters and setbacks, from Katrina in ’05 to the loss of our AAA credit rating and the government shutdown in 2011.

And yet, in response to each surprise, each major change, U.S. businessmen and women learned, adapted, and innovated. A few were even able to succeed at times when the markets greatly suffered, thanks to their long-term perspective.

Two weeks ago, I was privileged to have dinner with John Paulson, who made $15 billion on the sub-prime trade during the Great Financial Crisis. I asked him to tell me the story that evening of how the transaction evolved. He shared what it was like when he first saw the idea in ’05 and put the trade on, and how he missed on the timing and lost money. And then after putting it on again in ’06, how he not only lost money but also a few clients. Some believed he had gotten out of sync with the market.

At any moment he could have said, “I’m wrong,” especially if he had let himself be driven by what I’ve come to believe is the greatest destroyer of wealth: nervous energy.

But when you are confident in your theme and believe you are right, you have a chance to make a lot of money. When the markets turned in February ’07, John made 66% on his money that month. One of his clients called and said, “In the month of February you must have made 6.6%, not 66%… But you wrote 66.” To their amazement, John reassured them he meant what he had put. Not only that, the 66% was net — net of all fees. By doing that trade, he ended up making more than 1000%, proving true what Howard Marks said, that “Investing is extremely difficult. Timing is impossible.”

As incredible as that story is, the more incredible story is how we ultimately responded to challenges like the Great Financial Crisis.

Despite all the various leaderships, wars, cyber and terror attacks, regulations and rate volatility, booms and busts, the U.S. stock market not only survived, it thrived.

It powerfully persevered through four presidents of the Federal Reserve and four presidents in the oval office — two democrats and two republicans; through Clinton’s impeachment, Bush’s wars, Obama’s healthcare, and more recently, Trump’s three T’s: trade wars, tax reform, and tweets; through two recessions, three quantitative easings, and five bubbles. In fact, it out-performed every other market in the world during that time.

Goethe famously said, “Few people have the imagination for reality.” The rare ones see opportunity in times of distress and open new doors for the rest of us. Consider the Oil Shale revolution of ’03-’04, which changed our energy profile. Consider the search and social media revolution via Facebook and, of course, Google, with its five billion searches daily. Consider what we witnessed with mergers and acquisitions, as they increased dramatically during this period, resulting in approximately $4 trillion in 2018, and $55 trillion since 2000. Consider that $1.3 trillion was raised in initial public offerings, led by 548 IPOs in ’99, among the most ever in a single year. Consider that in only 25 years, that guy named Jeff grew Amazon beyond his garage to what is now a company with a market value of $1 trillion.

It’s no wonder that since 1994, the S&P is up almost seven-fold and the dollar (proudly) remains the world’s most dominant reserve currency. Take a moment to let that sink in. It’s a testament to the unique power of American capitalism.

There is no perfect system, but the great strength of American capitalism is that it enables someone with a vision to bring forth a product that is better for society — something that improves our overall standard of living and that is practiced under a rule of law.

Generation after generation we’ve seen our free market system generate growth that provides people with jobs and real opportunities to provide and advance. It allows our nation to handle extreme change, new problems, and to move forward in a way that adopts new technologies. Our free market continues to be a wonder to behold!

And yet, its blemishes are real — though they are largely the result of bad actors. Who can forget the damage done by Bernie Ebbers on Worldcom? Or Bernie Madoff and his pyramid scheme? Or even the colorful “Chainsaw” Al Dunlap when he ran Sunbeam? Before Al came along, we all knew two inventory accounting methods: LIFO (Last In, First Out) and FIFO (First In, First Out). Then Al’s deceptive imagination created a third: FISH — First In, Still Here.

But while the bad actors cause real damage, steal headlines, and have more movies made about them, they neither define nor dominate our free market. Brilliant capitalists do — people like Warren Buffet and Jack Bogle of Vanguard, who, as I mention them remind me of the long-running debate between active and passive investing. Exceedingly generous people do — including Gary Kelly and Jim Mulva, former Chairman and CEO of ConocoPhillips, who are as committed to giving their wealth back to the world as they are to defending capitalism. And there are many more like them than we realize, who are responsible for so much we benefit from.

Just take a walk around campus and you’ll see signs of them all over the place, as you go by the Cockrell School of Engineering, Dell Medical School, the Steve Hicks School of Social Work, and of course, the McCombs School of Business. These are the people who give our free market its character, conviction, and compassion, who are passionate about seeing the fruits of their success reinvested in worthy things. And they are also a big reason for my optimism and confidence for what lies ahead.

As much we would like to predict the future, it is never quite clear. We know great companies will continue to appear and booms are surely on the way; but we also know that busts will follow, and difficult surprises lie ahead, too. We don’t know what they are. We don’t know who will be running the country two years from now or how world events will redirect the story; we just know that they will.

What I do feel very confident about is that American businessmen and women will adapt through whatever macro environment they are given to deal with. I’m also confident they’ll be successful, and one of the main reasons for that confidence are places like the University of Texas.

Bob Rowling, whose name is on the hall we sit in tonight, has said many times, “The great equalizer, no matter where you start, is education.” I couldn’t agree more. When capitalism works well, it actually becomes true that no matter where you start from in society, it does not dictate where you finish. If we are serious about that being true in this country, then our universities are critical.

Schools like Texas know their responsibility to care for, impact, and serve the society of which they are a part. They understand their unique role to not only equip young leaders with the right foundation, but to also make them aware of societal gaps they can close through their work and service. It’s not just about improving our own personal outlook, but becoming equipped to go out and do the same for others. That’s a torch we are counting on you to carry — and I am speaking to all of the students here tonight. Opportunities will continue to abound for students like you to go out and make a difference and transform our country — that I am absolutely confident about.

We may not know what the next 25 years is going to bring, but there’s no question in my mind that the direction of this great state will be shaped in part by this great university. And as Warren Buffet said to me two years ago, “So goes Texas, so goes the United States, period.”

Ray Nixon is chairman of Nixon Capital and recently retired as the executive director and a portfolio manager at Barrow, Hanley, Mewhinney & Strauss LLC, one of the largest value-oriented investment managers of institutional assets in the U.S. He is also a member of the UTIMCO board of directors, which manages the $45 billion endowment for The University of Texas and Texas A&M. Nixon holds a BA and an MBA from The University of Texas at Austin and is a member into the McCombs Business School Hall of Fame. He is also a member of the McCombs Dean’s Advisory Council and is the co-chair of McCombs Capital Campaign.

About this Post

Share: