Final Management Lessons From Jim Fredrickson

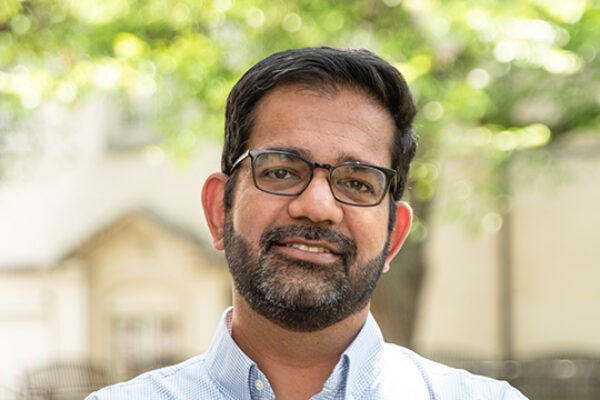

Shortly before his passing on July 23, Management Professor Jim Fredrickson looked back at his decades-long career at the McCombs School of Business to share some thoughts and insights.

Fredrickson, who was set to retire Aug. 31, joined the McCombs faculty in January 1990. He was a both world-renowned researcher and educator, earning over 20 teaching awards. He spent six years as chair of the Management Department, served on the department’s executive committee, and held numerous other professional appointments in his field.

Earlier this summer, Fredrickson shared his thoughts on the McCombs School of Business, his career, and management as both an academic and practical subject.

Looking back on your years at McCombs, what memories stand out?

Obviously, I’ve enjoyed a lot of things, including specific colleagues and classes of students. One highlight involves seeing a doctoral student go out and have real success and impact in their career. It’s always rewarding to see students have career success, but particularly so with doctoral students because of the unique relationship that can develop during an intense, many-years-long process.

It has always been a real high point when I finally see my research published in a top scholarly journal. These projects routinely take years from idea to execution, and then the written product must make it through a very demanding journal review process, where the chances of acceptance are routinely around seven percent. When they do and finally appear in print, it is tremendously rewarding.

You’ve taught many students over the years. What makes certain ones rise to the top?

It’s interesting how the dynamics in individual classes differ from one cohort to another. Often, the cohort has a group of folks who have emerged early in the first years as the informal leaders. They have great work habits and they’re smart, inclusive, and have high energy. Those people set the standard for the cohort.

How has management education changed over your career?

During the last decade, lots of schools and programs have put a major emphasis on entrepreneurship in the courses they offer and faculty research. So the rise of entrepreneurship has been a major change and theme in management.

What about the practice of management?

Increasingly, you’ll see tech companies like Google recruiting academics to apply analytical and research techniques. Practitioners continue to look for the silver bullet solution, even as they move from one hot topic to another. Academics tend to work on enduring issues. It happens in academia, as well, but the topics tend to stay hot longer — like a decade, not two years.

Academics’ standard for evidence is not the same as a practitioner’s standard. That’s often the source of conflict between the two: Practitioners are often looking for a clear, simple answer to a really big problem. Most really big problems don’t have clear, simple answers.

Do you see any big challenges for the field of management?

Generating student interest in management is becoming more of a challenge. My experience is that more MBAs are interested in creating an app that’s going to secure their future — not thinking of their careers as a progression through an organization or a series of organizations. And that has real implications. In my area of strategic management, you’re teaching them to develop the perspective of a general manager who’s responsible for running an organization or a multifunctional unit. So if you’ve got people who really don’t conceptualize the future as being tied to an organization, it changes things. To develop the skills of a general manager, you’ve got to develop your interpersonal and conceptual skills, well beyond technical skills. And that, in my view, poses a challenge.

How do you convince them that it’s really important to understand where you fit in the organization — and how the organization’s parts fit together — when the organization isn’t really a part of their thinking?

What advice do you have for upper management?

Top executives don’t design, make, sell, or service their products. The higher you go in an organization, the more your primary impact is what you say and do. Who do you promote or praise in public? What do you praise them for? What’s the message being sent if you preach about how important customers are but you couldn’t pick your customers out of a police lineup because you never interact with them? Executives should be sensitive to the symbolic effect of the things they say and do.

Maybe the CEO is talking about diversity and all his direct reports are white guys. Or staff morale is really low and he’s telling the troops, “Times are tough. We’ve got to get lean and mean. I know you haven’t had a raise in the last year and a half, but we’re in this together.” Then he leaves the meeting, gets in his limo, rides back to headquarters, takes a private elevator up to the 23rd floor, and has lunch in the executive dining room. The message obviously is, “You’ve have to get lean and mean — and I don’t.”

Do you have any key lessons you want your students to remember?

Companies are great not just because of product quality, the service they provide, or the profits they make, but in the values they perpetuate in the way they do business. The organization has an impact far beyond the product or the service — based on how we treat our customers and employees and the values we exhibit in the day-to-day way we do business.

About this Post

Share: