Titans of Realty

How Trammell Crow nurtured a generation of commercial real estate stars

By Jude Kinonen

Jeff Swope, BBA ’72, MBA ’74, recalls the Saturday morning in 1973 when he met Dallas real estate legend Trammell Crow. “I went in for an 11 a.m. interview, and by 11:10, he said, ‘I’m going to hire you.’”

Swope, now founder and CEO of Champion Partners Ltd., accepted in a heartbeat. He chuckles at his phone call three weeks later to Crow’s assistant: “I said to her, ‘I think I’ve been offered a job. Would you have a look through your file?’”

He had taken his first job without knowing exactly what he was going to do or even which city he would be working in. “We’re about to hang up, and I say, ‘Can I ask you one more thing? How much am I going to make?’” he says, laughing.

“All I knew was that I wanted to go work for Trammell Crow.”

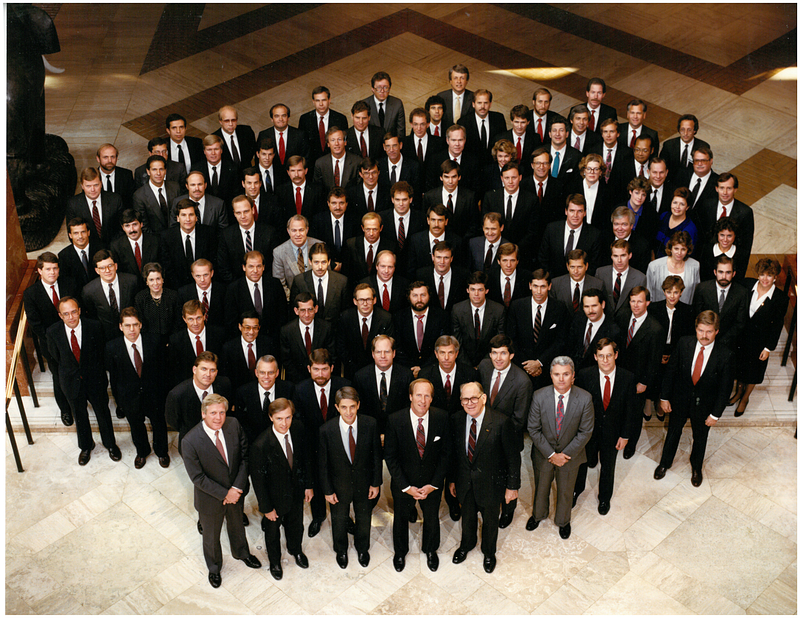

Swope’s story is echoed by dozens of McCombs’ most accomplished alumni who began their real estate careers with Dallas-based Trammell Crow Co., eventually becoming industry titans in their own rights.

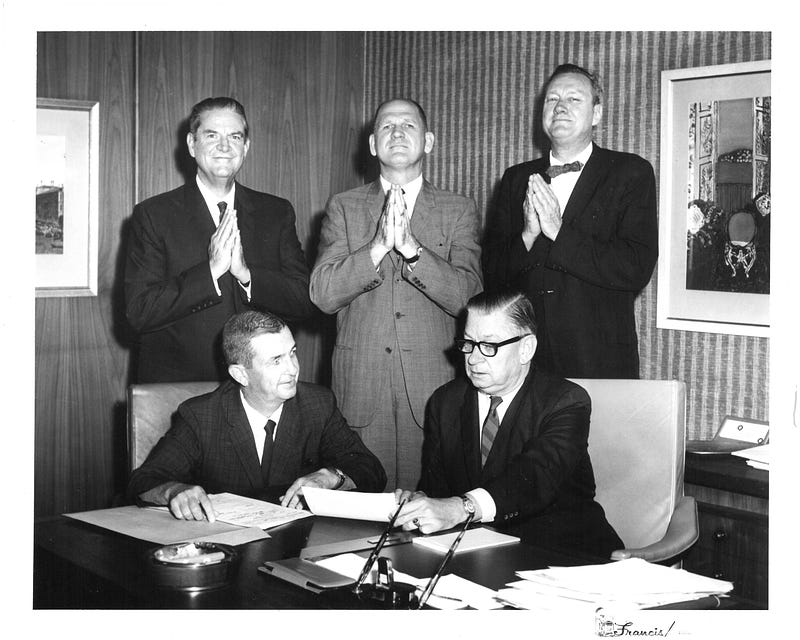

Crow was an accountant and World War II veteran who founded the company in 1948 with the construction of a one-story warehouse on the banks of the Trinity River. By the time of Swope’s job interview, the business had offices around the country, and by 1986, Crow was named the nation’s largest landlord by the Wall Street Journal. At the company’s peak, it held more than 300 million square feet in real estate.

But even more impressive is Crow’s lasting influence through those who trained under him, explains McCombs Dean Jay Hartzell.

“A huge number of people who started their own companies and have done all kinds of amazing things came out of that family tree,” Hartzell says. “My running joke when I meet a Texas real estate person is, ‘What did you do for Trammell Crow?’” In fact, a great number of the state’s top real estate firms today were founded by UT business alumni who got their start at Trammell Crow Company.

That comes as no surprise to Sandy Gottesman, BBA ’73, founding principal of Live Oak Development in Austin. “You could not meet Mr. Crow without thinking ‘I would love to work for him.’ It was obvious that he loved his work and his partners,” Gottesman says. “His warmth, sincerity, and enthusiasm were captivating. What I was going to get paid was secondary. When Mr. Crow asked how I was going to overcome the fact that I didn’t have an MBA and most of the other applicants did, I responded ‘Well, I guess I’ll have to get up earlier and work harder.’”

It was the kind of grit that Crow found irresistible. Indeed, Crow tended to hire entrepreneurial types — people who would eventually build their own businesses — and, in the late ’60s, ’70s, and early ’80s, he pulled most of them from Stanford, Harvard, and, of course, UT. In those years, UT was among Crow’s “happy hunting grounds,” Gottesman recalls. Graduates were likely to have strong character, high ambition, a friendly personality, and — just as important — a stomach for risk.

“You were taking a risk just entering the commercial real estate business at the time,” says Swope. “It wasn’t really considered a great job for an MBA because it was just a fledgling industry and totally fragmented.”

So Trammell Crow Co., with its emphasis on the relatively new arena of speculative building, attracted young people who were willing to trade the security of a steady paycheck at a large corporation for the chance of greater influence at a smaller, less structured company.

Marc Myers, BBA ’69, MBA ’76, founder of Myers & Crow Company Ltd., credits Ernest Walker, a long-time professor of small business in UT’s business school, for advising him and other entrepreneurial-leaning students to take jobs at smaller organizations. “In those companies, you might have more rapid advancement if you’re willing to take some risk,” Myers says.

“Crow was hiring a lot of guys who’d been in Vietnam flying airplanes and helicopters,” he adds. “He was looking for people who were friendly but didn’t fold under stress.” By the late ’70s, he had hired about 25 people — “who were eating nails for breakfast,” Swope says.

“They were betting on America in those years, which was a good bet,” says Harlan Crow, BBA ’74, Trammell’s son, who now serves as chair and CEO of Crow Family Holdings. “Of course there were mistakes — plenty of them — but more often than not, they were smart guys who did their homework, worked really hard, and made it successful.”

Myers says a young hire’s top priority at Trammell Crow Co. in those days was the cold-call. “We learned the business by going door to door to our tenants and other people’s tenants,” he says. In this way, they discovered which industries were growing, where they were located, and what drove tenant demand.

“Once you know where the demand is, and you know who’s looking, then you know what to build,” says Myers. “We learned the development business by always staying close to the market, measuring the market, talking with the tenants.”

The practice steeped this group of budding business leaders in an important concept: “You build what the market wants — not what you want, not what the architect wants,” Myers says.

The other important lesson learned, he adds, is optimism. Especially vital in speculative building, an “absolute faith in the future” colored Crow’s dealings, Myers says. “You have to have that if you’re going to build a spec building, because you’re building something before there’s a lease,” he says.

Crow also had faith in his team, and he was one of the pioneers of a generous profit-sharing model that made many of his young hires “partners” in his success.

Profit-sharing was not unheard of in those days, but it was not very common, says Harlan Crow. “Most people who went to work for a company back then earned a basic salary and maybe a bonus,” he says. “But my dad’s mentality was to share the profits, and he did share those quite liberally.”

Gottesman agrees. “Trammell was one of the most generous partners anywhere. The company gave young people more responsibility and more opportunity than we probably deserved,” he says.

He recalls one high-stakes deal early in his career — the Arboretum at Great Hills, an Austin mixed-use development with more than one million square feet of proposed office, retail, and hotel uses.

A number of the senior partners thought the project was too risky and that we didn’t have the local expertise for it,” Gottesman says.

After hearing a long list of reasons not to buy the land, Crow turned to Gottesman. “He said, ‘What do you want to do?’ And I said, ‘I want to do it.’ And he said, ‘So let’s go do it. I’m going to build the nicest hotel Austin has or ever will have.’ That was one of those moments when you just didn’t know if it was a dream or really happening,” Gottesman says.

Myers compares the rush of making a good deal to flying. “Not only did we think we were jet pilots, taking risk and flying fast,” he says, laughing, “but we thought we were carrier jet pilots.”

“Trammell Crow found these highly entrepreneurial people who absolutely had dominant personalities, loved the competition, loved the spirit of it all, and then they all wanted to go do it on their own,” Swope says.

The company, which went public in 1997 and was sold to CBRE in 2006, still actively recruits at UT, and two employees of Trammel Crow Co. serve on the McCombs Real Estate Center’s advisory council.

“If you think about the way people talk about pro sports, with coaching family trees and all the head coaches one team would spawn, there’s a certain equivalent here in the number of industry leaders who have been spawned out of the Trammell Crow Company,” Hartzell says. “And it turns out a lot of those people are Texas business graduates.”

From the Fall 2017 issue of McCombs, the magazine for alumni and friends of the McCombs School of Business at The University of Texas at Austin. Full PDF

About this Post

Share: