CEO Stories

Six McCombs BBA Alumni Share Secrets From the C-Suite.

By Chuck Salter

Gary Kelly thought he was ready. He’d been at Southwest Airlines for nearly 20 years, where he’d mentored under its legendary founder Herb Kelleher. He’d served as its CFO, which gave him insight into every aspect of the operation and every constituency, from the board to the banks to the unions. He’d been a vice president during the industry’s moment of crisis, the September 11 terrorist attacks, when the airlines were grounded. Now, for the first time in his career, Kelly wanted to be CEO. Believing he was the best prepared candidate, he considered it his duty to lead Southwest’s next important stage of growth.

But despite his seasoning and his confidence, when Kelly took the reins that year, in 2004, he was hit with the same realization as many a first-time CEO: Nothing fully prepares you. For the weight of accountability. For the complete reliance on others. For the endless challenges that have as much to do with psychology as business strategy. “It was a huge change,” Kelly says.

For such a high-profile position, where the hiring and firing and paying of many CEOs are well covered in the business press, the job itself remains largely opaque. To remedy that — and in honor of the school’s centennial — McCombs talked to a half dozen of the school’s BBA graduates who hold or have held the top job. Some, like Kelly, are longtime occupants of the C-suite. Others are so new that the ink on their business cards has barely dried.

In offering a candid glimpse into the reality of the job, they demystify the work itself and humanize those holding the lofty title. As undergraduates, they had a vague notion of what a CEO actually does on a day-to-day basis and of the path to becoming one. Later, they discovered how idiosyncratic the path is and how much the role itself can vary. The CEO is many things — many roles — depending on the company and the circumstances.

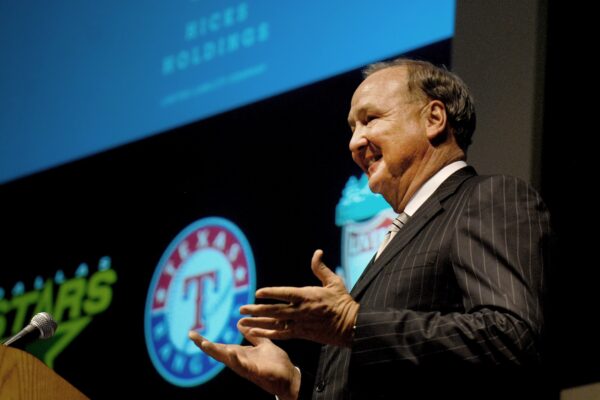

THE CORPORATE CEO

Gary Kelly, BBA ’77, Southwest Airlines

For the CEO of a company as large and complex as Southwest Airlines — with some 50,000 employees dispersed around the country — the job is often about finding ways to overcome its sheer size. Early on, Kelly had to relinquish his longtime role — and identity — as an expert. He had been Southwest’s controller at just 34 years old and eventually rose to CFO. If there was a budgeting or forecasting problem, he solved it. That’s what big-company department heads do.

When the board chose Kelly to run the Dallas-based airline, he had to make a critical shift: from depth of knowledge to breadth. “All of a sudden you realize you’re totally dependent on every member of the team,” says Kelly.

“I don’t fly planes or serve customers or change oil in the planes. There’s a long list of things I don’t know and I’m not proficient in. It’s humbling. Yet I’m responsible for all of the things that go on in the company.” — Gary Kelly

The key to overseeing an entire enterprise, as opposed to a single department, he says, “is knowing how much knowledge you need to gain, how many questions you need to ask, before you’re comfortable making a decision.”

Hear Gary Kelly’s story in his own words on McCombs Made, our monthly podcast featuring trailblazing McCombs alumni and friends.

Over the years, Kelly, now 61, has gotten comfortable with the resulting paradox, one that’s particularly acute for CEOs of large companies: The job entails both authority and vulnerability. Kelly may be the ultimate decider, but he bases his decisions in large part on what others tell him about what’s working at the airline and, more important, what’s not. “It’s the ultimate step in trust,” he says.

Consequently, Kelly focuses on sustaining a culture of trust, especially among department heads, that traces back to his early days as CFO. “When people make a mistake, they need to admit it, but that doesn’t mean they get shown the door,” he says. “Otherwise, it creates an environment of fear, and you won’t be getting the truth.”

Kelly has relied on that trust while making a number of major decisions in recent years: the $1.4 billion acquisition of AirTran Airways; the $250 million investment in a new reservation system; the addition of international routes, a first for the low-cost carrier; and a $1 billion-plus order for a new model plane from Boeing. With the latter, Kelly weighed the advantages of upgrading to more efficient engine technology and the risks of flying a new aircraft.

“It’s very different from being the №2, №3, or so on and making a recommendation to the boss, as opposed to being the one who has to choose,” he says. He’s always aware of the stakes for a company with nearly $20 billion in annual revenue and a streak of 43 profitable years. (Another streak to maintain: no layoffs in the airline’s history.)

But for all the focus on the price of fuel and the calculus of improving “passenger load factor” (the key measure of efficiency), Kelly’s day-to-day work sounds relatable at first blush. “I think people would be surprised at how non-technical a lot of my day is,” he says. “It’s pure people. It’s basic blocking and tackling and human relations.”

In his case, though, it involves vast numbers of people. “Hopefully, you’re inspiring them to a cause, and then inspiring them all to work together, and when you have conflict, to deal with it in a civil and respectful way,” Kelly says. “That’s a challenge. Our 50,000-member community is a society in itself.”

THE MAKEOVER ARTIST

Alice Schroeder, BBA ’78, MBA ’80, Webtuner

“Companies in denial about that are in denial about having their lunch eaten.” — Schroeder on how external forces affect your business model

Webtuber was on the verge of bankruptcy in 2014 when Alice Schroeder took over as CEO. The startup, based outside Seattle, in Redmond, had spent four years burning through its cash reserves while developing a product that had yet to come out — a device that streamed media over broadband. Management touted it as a breakthrough: It would offer four times more memory than Apple TV yet weigh a fraction as much. In a shake-up, WebTuner’s board brought in Schroeder, a former star analyst on Wall Street. She expected fixing the execution issues and cleaning up the balance sheet would turn things around.

Instead, Schroeder completely rewrote the business plan. She threw in the towel on WebTuner’s once promising hardware and switched to making software. The startup is starting over. “It took me over a year to make that decision,” she says. “If I could have done one thing differently, I would have done it all faster.” Instead of trying to salvage a broken business, she says, “I should have been asking, ‘If I had a blank piece of paper, what business would I choose to get into?’ ”

For a tech CEO, time is of the essence. The rate of change, she says, “is breathtaking compared to other industries. You never know if you have a competitive advantage. You have to be quite sure there’s something you’re doing that adds real value.”

Despite WebTuner’s head start on the industry, says Schroeder, manufacturing delays allowed Google, Amazon, and others to catch up on the technology and undercut the struggling startup on pricing. Schroeder’s new business model is a video aggregation service supported by ad revenue. “In the early 2000s, if you were a good news aggregator, that was a viable biz,” she says. “Now we’re in the same place with video.”

Schroeder is orchestrating this pivot despite no previous experience in tech or in the C-suite.

She does have a singular advantage, however: She wrote the book on Warren Buffett. Literally. In 2008, after some not-so-subtle nudging from him, Schroeder, once the top-ranked insurance analyst on Wall Street, wrote The Snowball, the bestselling biography of Berkshire Hathaway’s legendary chairman and CEO. “I spent years inside Berkshire Hathaway, hanging with Warren but also getting to know how some of his businesses work and understanding business models and seeing operational challenges,” she says. “They’re such diverse businesses, apparel to utilities, that it was like getting a Ph.D. I felt very prepared [as a first-time CEO].”

To her, one of the chief lessons from WebTuner’s troubles runs counter to Buffett’s hands-off approach, though.

“Recognizing how external forces affect your business model is the most important thing that you have to do as a leader. Companies in denial about that are in denial about getting their lunch eaten.” — Alice Schroeder

She also learned firsthand the isolation of the job. “Being a CEO is a very, very hard job,” she says. “You’re facing incredible obstacles, and when things are tough, you can never let it show in front of your employees. Your role is to make it all happen.”

THE DEALMAKER

John Goff, BBA ’77, Crescent Real Estate Holdings

“I learned to accept that uncertainty comes with every decision. You will never be able to get enough information to make it perfectly.” — Goff on making decisions

To John Goff, it was “the chance of a lifetime” — the Halley’s Comet of investments. In the early ’90s, following an unbridled building spree, the Texas real estate market was in the doldrums. Investors scattered to the winds. “We doubled the amount of real estate in the state in a 10-year period,” Goff says. “All this undisciplined capital led to bankruptcies and repossessions. The world was a mess.”

Goff, who was in his early 30s, suggested to his boss, billionaire investor Richard Rainwater, that they start a real estate company to take advantage of that mess. Quality real estate was cheap, Goff argued, and despite the glut, they could manage the properties well and profit handsomely after the downturn ended.

Rainwater agreed to fund the venture, as long as Goff put up everything he had — several million dollars. Goff took the gamble, becoming CEO of Crescent Real Estate Equities, a one-man operation based in Dallas. All he had to do was take his thesis, spelled out on a yellow legal pad, and sign on other investors. “It was very hard to find them, these unconventional real estate participants who believed in our strategy,” Goff says. “One attribute that people underestimate in a CEO is how important it is to be a good salesman. It’s not about hyperbole. You need the ability to sell your ideas.”

Goff proved adept at it. Within a few years, he had won over enough investors to amass a portfolio of more than three million square feet of real estate. Crescent’s IPO, in 1994, was one of the largest at the time for a real estate investment trust: The company raised over half a billion dollars.

From an early age, Goff had wanted to be his own boss. But he didn’t put a name to this — CEO — until later. As a boy, he’d seen the frustration of his father, a superintendent at Dow Chemical, who enjoyed his work but chafed at reporting to others. “That drove my passion,” Goff says. “I wouldn’t say I was a loner, but I was independent. I marched to my own drummer.”

After graduating from UT, he worked as a CPA before switching to business. As a young investor at Rainwater’s firm, Goff was drawn to the action, the deal-making of commercial real estate. “I wanted to shake up the industry,” he says.

Some of the gambles paid off beyond his wildest imagination, in particular the decision to sell Crescent in 2007 for $6.5 billion. Two years later, he and Barclays Capital bought it back for considerably less than his original sale price.

Despite the high stakes, he is comfortable with risk. It’s part of the job of a CEO, especially one in real estate. “I learned to accept that uncertainty comes with every decision,” says Goff, now chairman and CEO of Crescent Real Estate Holdings.

“You will never be able to get enough information to make it perfectly clear, which was tough because I tended to be a perfectionist. I wanted everything to be perfect. And it can’t be.” — John Goff

Which means that data only gets you so far. “You have to follow your gut,” says Goff. “It’s okay to have part of your decision be governed by some emotion.”

THE SMALL BUSINESS OWNER

Cindy Lo, BBA ’98, Red Velvet Events

“It’s working on the business versus working in the business.” — Lo on thinking like a CEO

The unexpected call was every event planner’s dream: The President’s coming to town — can you take care of it?

In 2012, in the heat of his reelection campaign, President Obama was scheduled to come to Austin for three fundraisers. All were top secret, requiring endless hurdles such as Secret Service clearance for each and every guest on the list — a Who’s Who of Austin. The person entrusted with pulling it off was Cindy Lo, the founder and CEO of Red Velvet Events. “A client of mine called and said, ‘There’s no way I’d do this without you,’” Lo says. “That’s when I realized, ‘Oh my gosh, we’ve made it.’”

The President’s visit went just as Lo planned. By then, she’d been in business for 10 years, but she didn’t feel like a CEO. She thought of herself as a small business owner, someone who wore multiple hats, who did whatever was needed at any given moment. Lo was a self-taught event planner who started her company in 2002 after leaving her job as a software project manager.

Hear Cindy Lo’s story in her own words on McCombs Made, our monthly podcast featuring trailblazing McCombs alumni and friends.

It wasn’t until recent years when she stepped back from every little detail and put together a leadership team that she felt differently. “It’s working on the business versus working in the business,” Lo says. “I started thinking like a CEO.”

Running a small business can be so demanding that the predominant leadership challenge is often finding time to lead — to be the CEO. When you start your own company doing nearly everything for yourself, it’s a hard habit to break.

For Lo, help came from a source familiar to CEOs everywhere: She joined a local CEO group offering support for those who find it’s lonely at the top. The executives and entrepreneurs in the group get together monthly to talk about work issues, off the record, and help each other out. “You talk about your highs and your lows,” she says. “If it’s a crisis, you see if anyone else has experienced it.”

When she joined the group, Red Velvet was its smallest company. She was struggling to grow, to surpass the elusive $1 million mark in annual revenue. But no longer. And in the last several years, Lo has gone from four employees to 20.

“Before, I was doing whatever I needed to do to survive,” she says. “But now we’re forecasting and thinking about how to sustain the company for five, 10, 20 years out.”

THE NEWCOMER

Kelly Steckelberg, BBA ’91, Zoosk

“There was a little bit of ‘Oh, how am I going to do this?’ I had to stop and remind myself, ‘You’ve had ideas every single day since you’ve been here about how to do things differently.” — Steckelberg on jumping into the role of CEO

Kelly Steckelberg’s first thought was, I don’t know how to be CEO.

It was a Friday afternoon in 2014, and she had been summoned to the office of the CEO of Zoosk, an online dating service based in San Francisco. He told Steckelberg that he and his co-founder were stepping down and the board wanted her to be the next CEO.

“There was a little bit of ‘Oh, how am I going to do this?’” says Steckelberg, Zoosk’s COO at the time. “I had to stop and remind myself, ‘You’ve had ideas every single day since you’ve been here about how to do things differently. And remember how much you’ve learned.’”

Steckelberg accepted the offer. “I love the mission of the company — we bring people together,” she says. “And it was an amazing opportunity as a woman to have the ultimate job.” Despite efforts to diversify the executive ranks, a female CEO remains a rarity in Silicon Valley and the tech industry at large. As if the position wasn’t hard enough for a first-time company head, the immediate priority at Zoosk was turning around a company still reeling from an aborted IPO. After filing the paperwork to go public, executives had canceled their scheduled road show. The winds of the market had shifted, from favoring fast growth — Zoosk had 30 million members after seven years — to favoring profitability. And the company still hadn’t made a dime.

Steckelberg began her tenure with the difficult task of laying off 15 percent of the 200-person staff. “Because I’m a finance person, I understand the health of the business,” she says. “So when the team asked, ‘Can’t we wait?’ I said, ‘No, we can’t, and I can articulate why. The sooner we fix this, the better, so we can move forward.’”

She is still learning on the job. Because she had never aspired to become CEO, she never consciously prepared for it. Her goal had been CFO of a public company. Accounting was her long-time specialty. After graduating from UT, Steckelberg spent several years at KPMG, one of the “big four” auditors. “What I loved was the exposure to a lot of industries,” she says. “You get to see a lot of different companies and learn how they’re run. Are they conservative or progressive? Risk averse or risk takers? It helped me see which environment I wanted to work in.”

She gravitated toward tech, spending more than a decade at fast-growing startups and rising through the management ranks. Her aspiration was taking a company public — “the ultimate thing you can achieve as a CFO,” she says. At Zoosk, she thought she’d have the chance.

She still might. But for now, Steckelberg is focused on maintaining the company’s recent momentum as it gets costs under control. After five quarters (and another round of layoffs), Zoosk finally grew subscriptions and bookings (dates arranged through the app) at a profit earlier this year. “We’re getting to a better place,” she says.

THE BUILDER

Sam L. Susser, BBA ’85, Susser Holdings

“One of our board members urged me to think hard about what decisions I wanted to keep control of. He squeezed his hand in a fist and said, ‘Hold onto those like you’re squeezing the life out of a chicken, but let go of everything else.’” —Susser on critical advice for any CEO

His father didn’t say a word. Sam L. Susser saw in his dad’s eyes what needed to happen. Sam should leave Wall Street and come home to help save the family business.

The year was 1988, and the banks had called a meeting to determine the fate of Susser Petroleum Company, the fuel, convenience store, and real estate business that Sam’s grandfather had started following the Great Depression. Fifty years later, the enterprise was on the brink of bankruptcy, undone by the collapse of the energy, real estate, and banking industries in Texas. Because Sam’s father, Sam J. Susser, BBA ’62, and uncle, Jerry Susser, had personally guaranteed the company loans, the family was facing financial ruin.

Sam, a 24-year-old analyst at Salomon Brothers in New York, quit his job and returned to Corpus Christi to help his uncle, who was running the company. (His father, president of Citgo Petroleum, needed to keep his steady and lucrative income.) The core business, selling motor fuel, was in free fall. “I had to engineer a plan for survival,” Sam says.

To pay off the debt, his plan involved enlisting more than a dozen outside investors to help start a new company, later Susser Holdings, built around the family’s one cash-flow positive business: five convenience stores in Texas. Susser, whose family retained a 30 percent stake in the new entity along with its original wholesale fuel business, then spearheaded an effort to “grow our way out of the problem,” he says, by acquiring half a dozen 7-Eleven stores.

Things improved. A few years later, at 28, Susser became CEO, a job he’d hold for the next 22 years. (He also served as CEO of the wholesale fuel business.) As the business generated more cash, he accelerated the expansion of the convenience store chain, Stripes, doubling overnight on four occasions through acquisitions. Ten years in, he bought out his father and uncle and the early investors who had enabled the company to survive.

In 2012, with more than 500 stores and nearly $5 billion in annual revenue, Susser Holdings cracked the Fortune 500. In 2014, when Susser decided to sell the company to the oil giant Sunoco, it had grown to 650 stores in Texas, New Mexico, and Oklahoma, nearly $7 billion in revenue, and some 12,000 employees.

Throughout his career, rapid and massive growth forced Susser to continually adapt. The organization outgrew his early hands-on approach. (The first year, he’d actually delivered donuts to the stores himself.) Susser, regarded as one of the industry’s leading innovators, embraced technology to better manage the sprawling organization. “Our biggest competitive advantage became our analytics,” he says. “We knew every keystroke on the register, the length of time of each transaction, what was selling in each store.”

He also learned the key to delegating — critical advice for any CEO. “One of our board members urged me to think hard about what decisions I wanted to keep control of,” Susser says. “He squeezed his hands in a fist and said, ‘Hold onto those like you’re squeezing the life out of a chicken, but let go of everything else.’”

Today, Susser is a former CEO — in some ways, a reluctant one. “My wife [Catherine G. Susser, BBA ’91, MPA ’91] and I didn’t want to sell the business,” he admits. “But after months of painful reflection, we came down on the side of this is something we had to do. We had a fiduciary responsibility to investors.” After all, Sunoco paid nearly $2 billion.

But Susser, 52, is also experiencing the upside of leaving the CEO lifestyle behind. For years, he spent half of every month on the road, away from his wife and three children. “I missed the window on my first born,” he says of his daughter, Sophie, a freshman at McCombs. “But I’m spending more time around my boys. I wasn’t making Boy Scout camping trips when I was running a Fortune 500 company.” But he is now.

From the fall 2016 issue of McCOMBS, the magazine for alumni and friends of the McCombs School of Business.

Originally published at www.today.mccombs.utexas.edu.

About this Post

Share: