The Kozmetsky Effect

How a tech visionary transformed McCombs and helped create the modern Austin

By Steve Brooks

The year was 1971. The phrase “Silicon Valley” had just debuted in the press. In Austin, a group of business leaders were sitting down to dinner at the downtown Ramada Inn to hear one man’s vision of Austin’s tech future.

That man was George Kozmetsky. He had come to the University of Texas business school in 1966 from his California technology conglomerate,

Teledyne. That night, he forecast that what was happening around San Jose, California, could happen in Austin. If local businesses, governments, and the university collaborated to attract manufacturers and nurture entrepreneurs, he explained, Austin could become its own technological center.

The opportunities were so great, he added, that he was surprised it had not already happened.

“His idea was not to lose our best and brightest to Silicon Valley,” says John Sibley Butler, McCombs management professor and longtime Kozmetsky associate. “His vision was, ‘How do we create wealth and create jobs? We do that through science and technology.’”

In the ensuing decades, Kozmetsky helped make that vision happen. “As Austin continues to reinvent itself, all efforts are simply footnotes to the ideas of Kozmetsky,” Butler says.

It’s hard to imagine a McCombs faculty member or dean with a more lasting influence on the school and his adopted city than the late dean. His combination of vision, innovation, and excellent timing help explain his legacy.

Among his contributions were elevating the business school to national prominence while serving as its second-longest-tenured dean, from 1966 to 1982; founding the IC2 Institute, a think tank on technological entrepreneurship in 1977; helping recruit to Austin the computing

research consortium Microelectronics and Computer Technology Corp. (MCC) in 1983; launching the Austin Technology Incubator (ATI) and the region’s first venture capital network in 1989, while running IC2; and mentoring entrepreneurs such as Michael Dell and serving as one of his first two directors.

“He didn’t always know how all the parts would fit together, but he knew he wanted to develop this as an entrepreneurial, technologically advanced hub,” says Robert Peterson, McCombs marketing professor and IC2 director from 2013 to 2016. “I would describe George as a visionary.”

The Road To Texas

Kozmetsky spent half a century developing his vision before he ever got to UT. Born in 1917 to Russian immigrants in Seattle, he was a medic in World War II, got a Harvard University MBA, and taught at Carnegie Mellon University before joining the business world as an accountant at Hughes Aircraft.

He spent 14 years in the Southern California technology scene. Building computers for Litton Industries inspired him to co-found Teledyne in 1960. His startup rocketed into the Fortune 500, developing navigation systems

for U.S. Navy helicopters and electronics for Apollo moonshots.

Teledyne also manufactured semiconductors in Mountain View, California, near San Jose. “He was familiar with the early years of Silicon Valley,” says biographer Monty Jones. “He had seen the intimate relationships between

business, academics, and government, and it led him to want to do it himself.”

When Los Angeles erupted in riots in 1965, Kozmetsky was ready to move on. He believed business should solve social problems as well as reward investors. His wife, Ronya, a former social worker, encouraged him to return to academia, just as UT was seeking a business school dean.

Transforming the Business School

Kozmetsky arrived at UT in the midst of a 10-year plan to elevate itself from a regional university to a nationally ranked school. The UT System Board of Regents charged him to do the same for business.

“We were teaching people how to run the Firestone store back home,” says William Cunningham, who succeeded Kozmetsky as dean and was UT president from 1985 to 1992. “George was more interested in how you could

create an Apple Computer.”

It helped that, as a fellow businessman, he had the regents’ ears. They created an economic advisory position for him, counseling the board on topics from investing university funds to buying supercomputers.

After one board meeting, a regent said, “I don’t understand it, but if it’s OK with George, it’s OK with me,” Jones says.

With the administration’s support, Kozmetsky recruited faculty members from schools such as Harvard and Stanford University, luring them with research money and endowed professorships. During his tenure, endowed positions mushroomed from two to 23.

He also worked to diversify the faculty and student body. Vijay Mahajan, a professor of marketing, remembers applying in 1972 to be the first Asian Ph.D. student. One staffer questioned spending public funds to educate someone who might go back to India. Kozmetsky learned of the discussion and said, “Admit him.”

While raising money from business leaders, Kozmetsky also contributed personally. UT records show that he and his then-named RGK Foundation, which was directed by his wife, gave more than $16 million to business school programs.

Other innovations included a new building for the Graduate School of Business and an Executive MBA program, letting area executives earn a degree without pausing their careers.

By the time he retired as dean in 1982, the seeds were planted to make Austin the “Silicon Hills,” and the school was on its way up. A nationwide survey of business deans in 1979 rated UT’s undergraduate business program as the fifth best nationally. A separate survey of business professors in 1980 ranked its faculty the seventh best.

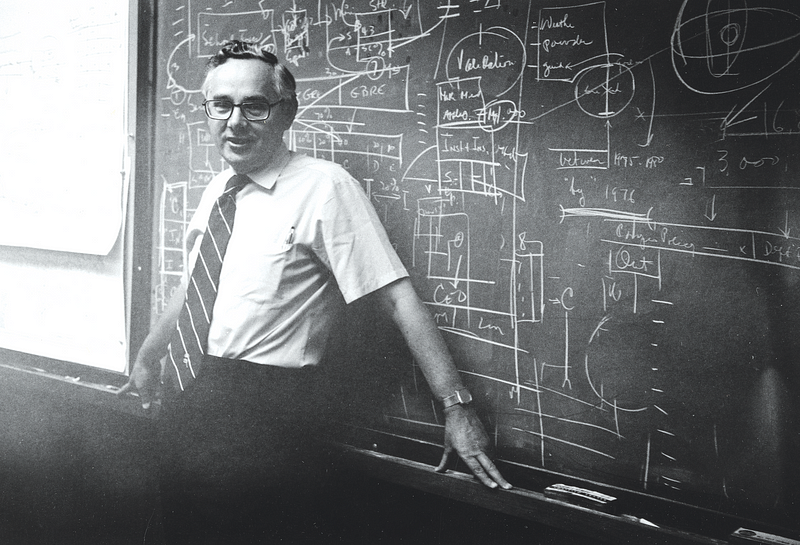

Blackboards and Polaroids

Business school col leagues remember Kozmetsky’s workaholic routine as more like a CEO than an academic. He regularly came to the office at 4 a.m., leaving the front door locked. People seeking an audience came early, sometimes tossing pebbles at his window to be let in.

His communication style could be notoriously hard to follow. “George always started conversations in the middle of a paragraph,” Cunningham says. “His mind was racing so fast that, by the time you entered the room, he was halfway through the subject.”

To keep track of his ideas, he often wrote on a blackboard as he talked. “He would call me in to take a Polaroid photo of that blackboard so he would know what he had discussed with someone,” recalls Ophelia Mallari, his administrative assistant.

Over time, his thoughts ran further and further beyond the business school. He started IC2 in 1977, describing it as a “think and do” tank.

Butler recalls being involved with Kozmetsky in planning the new institute, which Butler would one day lead. “We sat up there on the top floor of McCombs, and he drew Austin out, the way it looks today,” Butler says.

When Kozmetsky left the dean’s office five years later, it was to run IC2 full time. He turned his attention to his broader vision: creating what he called the Austin technopolis.

Transforming Austin and Beyond

To Kozmetsky, the name IC2 meant Institute for Constructive Capitalism, a concept he’d learned at Harvard.

“He very much believed in capitalism and wealth generation,” explains

Laura Kilcrease, founding director of the Austin Technology Incubator and several of his other initiatives. “He also felt that, where possible, he should participate in helping others. How could we achieve a growing and diversified economy where everyone has jobs and has a style of living that suits them?”

For Kozmetsky, the answer was to build a business ecosystem that cultivated tech entrepreneurs. He spent his last two decades putting

pieces into place and seeing them flourish. MCC pioneered cutting-edge

computing technologies. ATI nurtured business startups. The Capital

Network matched startups with investors. The Austin Technology

Council gave the industry a network and a policy voice. And a Master of

Science in Technology Commercialization at McCombs trained executives

to tap university researchers to move products into the marketplace.

But his vision wasn’t confined to Austin. “At IC2, we always considered

Austin an experiment,” says Butler, who directed the institute from 2002 to 2013. “The Austin Model had an international reach.”

For 14 consecutive summers, he and Kozmetsky presented programs in Japan. IC2 also put on entrepreneurial workshops in China, Brazil, and Poland; started incubators in India and Kazakhstan; and opened an office in Monterrey, Mexico.

A Skyline and a Legacy

Although Kozmetsky died in 2003, his work lives on. McCombs remains

nationally respected, with its accounting program ranked first in the nation and its BBA ranked fifth by U.S. News & World Report. IC2 is celebrating its 45th year of researching and catalyzing economic development.

Perhaps his most visible legacy is the Austin skyline, transformed by his vision from five decades ago, along with 155,000 regional tech workers now toiling in the technopolis.

Kozmetsky’s legacy is underscored on the National Medal of Technology

the White House awarded him in 1993. It says, “For his commercialization

of various technologies through the establishment and development of over one hundred technology-based companies that employ tens of

thousands of people and export over one billion dollars worldwide.”

Peterson puts it more succinctly. “Where we are in Austin today is in part a reflection of George’s vision. Without George, would all of this have happened?”

Butler doubts it. “I look around Austin today, when I’m stuck sitting in traffic, and I curse George.”

Steve Brooks is a veteran Austin journalist and musician who has written for McCombs since 2010.

This article appeared in the Centennial 2022 issue of McCombs magazine. Click on the link to see the full issue.

About this Post

Share: