Awesomeness

Powerful experiences can help us realize how much we don’t know and fire creativity

Sunrise glinted over the horizon of Bryce Canyon. It started to bathe an amphitheater of amber, peach, and vermillion hoodoos in rosy beams until they seemed to glow by themselves.

Astoundingly ancient and titanically tall giant sequoias — some as high as the UT Tower — reached for the dome of the sky, creating their own treetop ecosystem in majestic upper branches.

Duke Ellington and then Cocteau Twins wafted from a portable cassette player as my son and I swayed around the hospital room during his first day in the world.

What binds each of those moments together for me? They were awesome. They were the embodiment of “you had to be there.” Clearly, I don’t mean awesome in the pedestrian, offhanded way that characterizes the word in today’s everyday speech. If everything is awesome, then nothing is awesome. My kids mutter “awesome” when I buy them new socks.

Instead, those moments sparked wonder and amazement. They made me pause and take them in. They were astonishing if not literally staggering. Just as importantly, and as part of the scientific definition of awe, the moments humbled me. If an experience is truly awesome, it makes us feel small relative to something outside of us that feels vast. Having my own newborn in my arms was assuredly that.

Turning to what awe(someness) is not, it doesn’t have to be a dopamine jolt from a positive event. It can be an experience that’s monstrously scary. Think of facing the wave in “The Perfect Storm,” or of having to watch Pauly Shore movies every day for eternity. It also doesn’t have to be physically gargantuan. My newborn son was just the opposite.

You might justifiably ask, “Dude, what does this have to do with research?” As part of a series of ADR columns on the genesis of Big Ideas™, I’m observing that social science evidence shows that awe serves as a spark for creativity and novel ideation. And surprisingly, awe creates as powerful a cognitive response as an emotional one. The gobsmack of awe cues us to realize how much we don’t know. Awesome events are enigmatic. They require accommodations to our mental structures that push us to think in broader and more divergent ways.

So, the next time you’re pondering research topics or developing theory, first go experience something awesome … before you buy your kids new socks.

I’m not going to cheapen Tim Werner’s work by saying it’s awesome, even though it is — and possibly in a fear-inducing way. But it is great to have him at McCombs, telling the rest of us how partisan politics is becoming part of the bloodstream of business.

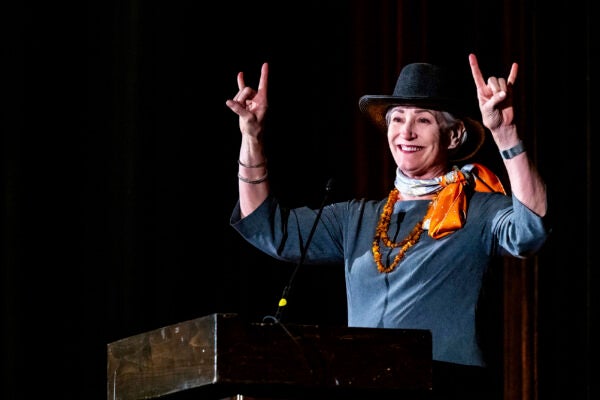

Dr. David A. Harrison

Associate Dean for Research

About this Post

Share: