Adjusted Earnings Don’t Fool Investors

When companies omit stock-based compensation to make earnings look better, investors fill in the missing numbers

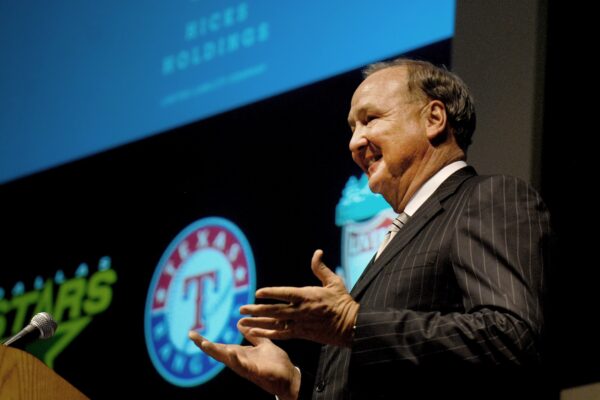

Based on the research of John McInnis

When companies massage earnings reports to make profits look larger, do investors buy it? In some cases, they don’t. That’s the lesson from new research by John McInnis, professor of accounting at Texas McCombs.

The results are “comforting,” he says, indicating that current accounting rules give investors enough information to make informed decisions.

His research looked at a common corporate practice: presenting two different sets of earnings to the public.

Official financial statements such as 10-Ks follow generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), which the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) requires for all U.S. public companies.

But a company can present an alternative earnings report in press releases and analyst calls, as long as it explains what’s different. Such non-GAAP reports leave out some kinds of expenses — and they generally boost earnings.

How common is the practice? A 2024 report found 80% of the companies in the Dow Jones Industrial Average presented non-GAAP earnings. Those numbers averaged 31% higher than GAAP earnings.

To GAAP or Not to GAAP?

GAAP, set by the nonprofit Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), lets investors compare companies’ financials on an apples-to-apples basis. It requires inclusion of all expenses, from stock options to depreciation.

But those expenses are sometimes temporary ones — such as restructuring — that slash net income for a single quarter. Companies exclude them from non-GAAP results to show what income would have been otherwise.

“I want to tell investors that my income this year was low because of a one-time charge, not because the core business is weak,” McInnis says. “The vast majority of non-GAAP reporting is not opportunistic. Generally, it seems to be informative to investors.”

But some exclusions are more controversial, because they’re recurring and may stay on income statements for years. One such expense is stock-based compensation (SBC), such as stock option awards to executives.

SBC can be a large item. In 2024, Alphabet — Google’s parent company — reported $23 billion.

GAAP accounting required companies to report SBC 20 years ago, after scandals like Enron pushed regulators to increase transparency. But that hasn’t stopped many companies from dropping it from non-GAAP reports, inflating their apparent income.

Do Investors Notice?

“Most accountants agree stock options should be treated as expenses,” McInnis says. But he wanted to find out whether investors felt the same. Did they notice when companies omitted large stock awards from non-GAAP earnings — and price the companies’ stocks accordingly?

To investigate, he and Laura Griffin of the University of Colorado Boulder analyzed over 70,000 quarterly earnings announcements involving SBC from U.S. public companies between 2003 and 2021.

Using automated text analysis of press releases, they looked for cases in which companies excluded SBC items. They analyzed the companies’ stock performance around those announcements.

They found that companies reporting unexpected increases in SBC saw lower short-term stock returns, ranging from 1 to 2 percentage points. Importantly, this penalty for higher SBC was no different for companies that excluded SBC from their non-GAAP figures.

The researchers found similar results for another kind of recurring expense that’s often left out of non-GAAP reports: amortization of intangibles from acquisitions, such as the value of patents and licenses.

To McInnis, the results suggest that investors do pay attention and factor in costs such as SBC, even when companies are leaving them out.

“There’s a belief on the street that if you exclude these things, investors will give you a higher valuation,” he said. “That appears to be mythology.”

That’s good news for the groups that write and enforce GAAP, McInnis adds. “If I were at the FASB or the SEC, I’d be pleased to see this. It wouldn’t be a call to action to tighten the rules. If anything, it’s reassuring that the system seems to be working.”

“Gone but Not Forgotten: Investor Reaction to ‘Excluded’ Recurring Expenses” is published in Journal of Accounting and Economics.

Story by Hope Reese

About this Post

Share: