Do We Overeat Because It’s “Healthy”?

Terms like “all-natural” and “organic” may actually trigger overeating.

By Adrienne Dawson

Before you even consider a food’s calorie count, you’ve probably already decided to eat too much of it. That’s one of the key findings from the McCombs School of Business’ Jacob Suher, Ph.D. ’16, and Marketing Professors Raj Raghunathan and Wayne Hoyer.

Earlier research links overeating with calorie counts: The fewer calories an item is perceived to have, the more likely we are to eat too much of it. But some studies manipulated healthiness without including calorie labeling and failed to consider how people make choices in real-world settings. So Suher and his colleagues set out to uncover the unconscious drivers that influence our decisions about food.

In a series of studies examining how people make food choices, the researchers found that the associations we have with specific foods — and, in turn, what words we use to describe those foods — influence how much we think we need to eat in order to feel full. Our desire for satiation triggers an unconscious decision to eat more of certain foods regardless of how many calories the label says they have.

Healthy = Less Filling

First, Suher and his co-authors conducted a preliminary test to gauge these associations by having people use a computer to categorize foods as quickly as possible. They looked at participants’ reaction times in milliseconds — how quickly (or slowly) people rated common foods like salmon or donuts as either “healthy” or “unhealthy” and “filling” or “not filling.”

Suher explains: “For example, if we show people a picture of broccoli and the word ‘filling,’ they’re slower to move those two items to the same side of the computer screen. That tells us they have to think about it longer. It’s not a natural association. On the other hand, if we show someone a picture of a cheeseburger, they’ll rate it as ‘unhealthy’ and very quickly move it to the ‘filling’ side of the screen.”

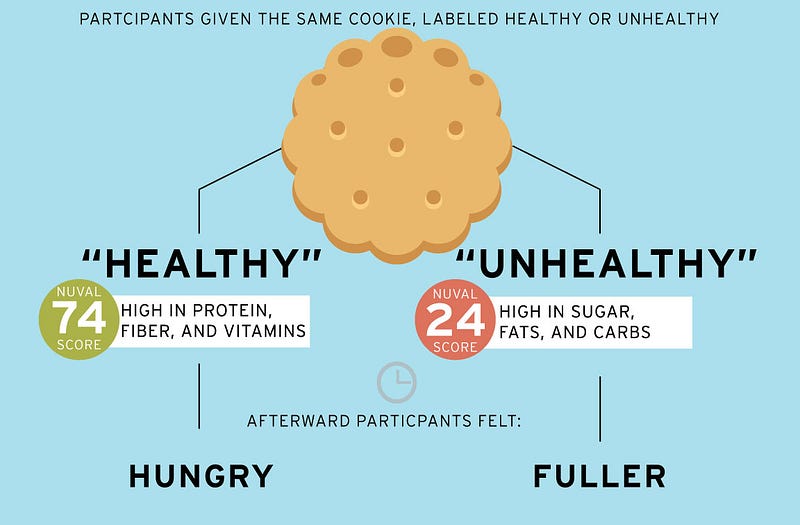

Next, the researchers wanted to see how these associations affect actual food choices. In one study, they gave participants cookies that were individually wrapped in their original packaging. But each participant also received a piece of paper with different descriptions of the cookies. Some cookies were described as “healthy” with a NuVal score of 74 and were said to contain “high levels of protein, fiber, and vitamins.” Other cookies were described as “unhealthy” with a lower NuVal score of 24 and were said to contain “high levels of sugar, fats, and carbohydrates.”

The NuVal system scores food on a scale of 1–100. The higher the NuVal Score, the healthier the food.

In both cases, participants had the actual caloric and nutritional content provided directly on the product packaging, and although those details were the same for every cookie, people rated their hunger levels differently depending on which description they received. Those with the “unhealthy” cookies said they felt fuller both immediately after eating the cookies and again 45 minutes later.

Those who’d eaten the “healthy” cookies, however, reported that they were still hungry.

“Healthy” vs. “Nourishing”

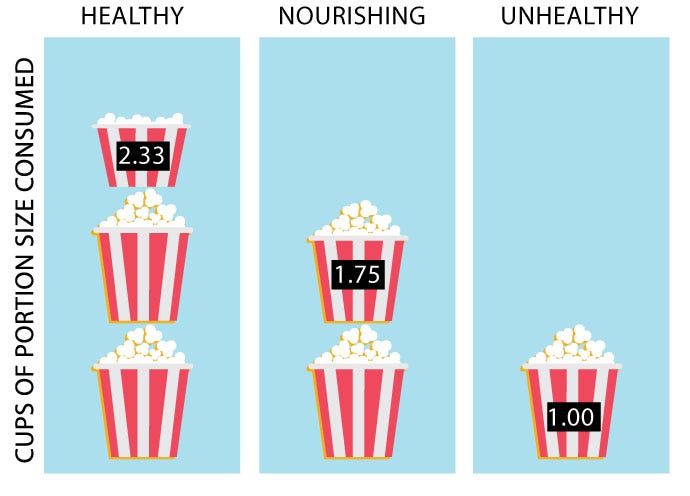

In another study, participants were asked to watch a video and were told they’d be provided with popcorn as a snack. The popcorn was the same for all participants, but the popcorn was described in three different ways. Everyone was told that it had 50 calories per cup, but some were told the popcorn was:

• “Healthy” and had a NuVal score of 74;

• “Nourishing” and had a NuVal score of 74; or

• “Unhealthy” and had a NuVal score of 26.

Each participant could order as much popcorn as they wanted (up to 10 cups). As expected, people who were told the popcorn was “healthy” ordered and ate significantly more than those who were told the popcorn was “unhealthy.”

But, in a twist, participants who were told their popcorn was “nourishing” also ordered and consumed less than the “healthy” subgroup.

“What we find is that there’s another mechanism besides calories that’s contributing to this tendency to overeat,” says Raghunathan.

“People think that if something is healthy, then it can’t be filling, and we call this the ‘more healthy = less filling’ intuition. Because we harbor this belief, we end up eating more of an item when it’s portrayed as healthy.”

— Raj Raghunathan

On the other hand, when an item is described as being “nutritious,” people seem to attach a different association to the food. They order less, and they eat less.

Don’t Fall for the Health Hype

“We see this research as being aimed primarily at consumers,” says Raghunathan. “Being aware of these different messages and beliefs about food may help mitigate the tendency to overeat.” And it isn’t just the word “healthy” that might trigger overeating, he adds. Terms like “all-natural” and “organic” may elicit the same kinds of unconscious associations.

But while the biggest lesson is for consumers, there are takeaways for marketers, too — namely, know your customer. “If making money is your only objective, then portray your food as ‘healthy’ because people will consume more of it,” Raghunathan explains. “But that could backfire eventually if customers are consuming too much of an otherwise ‘healthy’ food and are gaining weight.”

Suher agrees. “Be sensitive to what your customers want and expect. If they want healthy food, you can help them out by showing them that it’s also nourishing so they won’t over-consume it and may be turned off in the future. For those customers who value feeling full, our work suggests that portraying it as nourishing as opposed to simply being ‘healthy’ could help acquire those customers.”

Adds Marketing Department Chair Wayne Hoyer, “These findings are illustrative of the growing recognition that subtle changes in the environment can have a major impact on consumers’ behavior and that one way to change people’s eating habits is to alter the context in which food is presented.”

Originally published at www.texasenterprise.utexas.edu on May 20, 2016.