Wild Journey

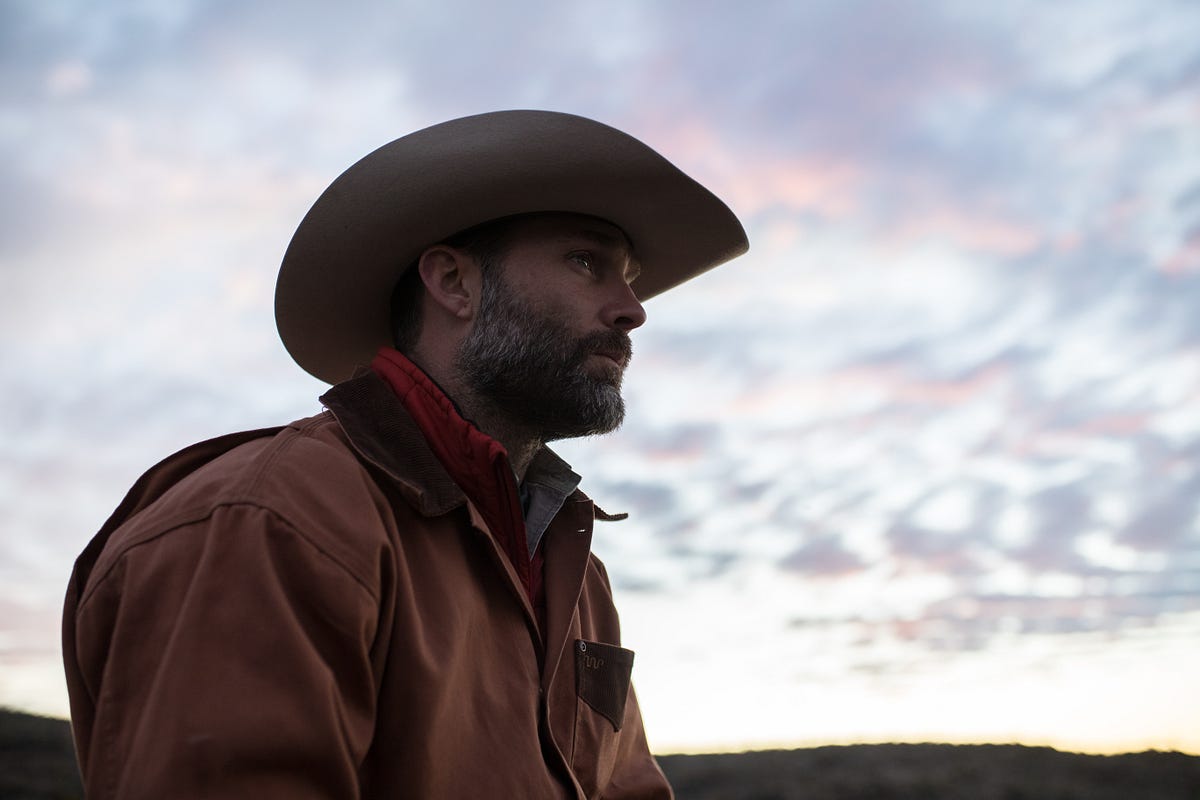

Sixth-generation Texan Jay Kleberg, MBA ’13, son of a storied Texas ranch family, turns his love of the land into a grand adventure.

By Todd Savage

Jay Kleberg, MBA ’13, recalls a time in his early 30s when he was working as a business development director for a real estate investment trust. The El Paso-based company developed industrial parks along the U.S.-Mexico border, and Kleberg was in Chicago touring a 3-million-square-foot industrial park. “It was the last place on earth I wanted to be,” he recalls.

But one of his colleagues had a different attitude. “He was just ecstatic looking at the bay doors and the quality of the buildings, looking at all the aspects of this park like a piece of art. I thought to myself, ‘I need to figure out another career path,’ because obviously this guy really loves this stuff.” Kleberg knew he needed to find something that sparked his passion in the same way.

“Hitting a reset button” was what Kleberg decided he needed to do, so he applied and enrolled in the Texas McCombs MBA program. Soon after arriving at UT, he was sitting in a class with the popular Senior Management Lecturer John Doggett, who asked everyone to think about how they wanted to be remembered. “If the slate is clean, then I want to be remembered for making a difference,” Kleberg says. “It got me thinking.”

What it got him thinking about was his upbringing and the issues he cared about. Kleberg, now the director for conservation initiatives at the Texas Parks and Wildlife Foundation, grew up around open lands and wildlife. Once he left his family’s ranch, he spent time exploring the wider world — getting his B.A. in English literature at Williams College in Massachusetts, spending three years in Brazil, getting his pilot’s license, and later pursuing real estate work — but when Doggett asked the question, Kleberg knew in an instant that he needed to go back to his roots.

“I have a passion for conservation and stewardship that has been passed on to me,” Kleberg says, meeting for an interview at Austin’s South Congress Hotel. As he talks, he often gestures toward large photographs on the wall of the canyons of the Rio Grande.

Compared to families with parents who came home from work every evening at 5:30, Kleberg’s childhood was distinctly different. A sixth-generation Texan, he grew up on the King Ranch, the storied and sprawling South Texas property founded by his ancestors in 1853 that today is spread over 825,000 acres and is home to 35,000 cattle.

When Kleberg was growing up, his father was responsible for managing global farming and cattle operations for the ranch. Geneticists, biologists, and cowboys passed through their home. Dinner conversation topics touched on cattle and quail, grasses and land management. His parents took him out of school to work cattle roundups and travel to stock shows with the quarter horses they showed, and he was taken out with cowboys branding, castrating, and herding cattle.

“It was all-encompassing,” says Kleberg, dressed in Texan business attire of crisp button-down shirt, Wrangler jeans, and cowboy boots. “I was surrounded by cowboys and cowboys’ children. There were biologists working on improving native habitats. It was just part of growing up.”

The ranch has had a long relationship with Texas McCombs. In 1983, the King Ranch Family Trust endowed the creation of a professorship. In 2015, it was expanded and renamed the King Ranch Chair for Business Leadership, a position now held by Senior Associate Dean Eric Hirst.

After getting his MBA, Kleberg learned how valuable his business education was for a nonprofit organization like the Texas Parks and Wildlife Foundation.

“There definitely is a real need for analytical, strategic thinking, and an ability to think about public access and funding. It’s about taking all of the things that we’re learning in business school but applying those skills to the natural world.”

Indeed, his first task at the foundation was writing a business plan as part of a campaign to raise $100 million.

In the role, he works to manage philanthropic donations to acquire new land for public access. Then he oversees a team to perform habitat improvement, such as restoring coastal prairie near Port O’Connor along the Gulf of Mexico at the 17,000-acre Powderhorn Ranch. “I’m trying to enhance public access and conserve native habitat in Texas and do that by any means possible,” he says. “Many of the national and state parks exist due to generous donations of individuals. Big Bend National Park, Padre Island National Seashore, Big Boggy — all of them started with private citizens.”

He’s learned that even donors in the area of land conservation are thinking of their contributions as investments. He explains: “They want metrics about how much habitat you’re restoring, what’s your baseline, and how many ducks or quail or deer are being conserved, or how much water is flowing now that wasn’t flowing before? If we’re going to put money to work, then how do we maximize our impact and how do we measure all of that? Again, we’re taking what everyone is learning at business school and just applying it to a different industry.”

His work has taken him to far-flung corners of the state. He knows the Texas landscape well, but in the winter of 2017, he got a more intimate look at one of the state’s most fabled natural features: the Rio Grande. The river defines the state’s 1,200-mile border with Mexico, as its leaves El Paso on the state’s far northwestern corner on its way to the Gulf of Mexico.

Kleberg and four others — a filmmaker, an ornithologist, a wildlife videographer, and a whitewater rafting guide — embarked on a 72-day journey traveling the entire length of the river to make a documentary exploring the border. Kleberg brought his knowledge as a conservationist to the team — not to mention his experience on bike, horseback, and canoe. The group traveled along the river pedaling mountain bikes on muddy paths, trekking up and around rocky canyons astride beautiful mustang horses, and finally paddling canoes through walled canyons rising to 1,500 feet and rock-filled rapids until they reached the confluence with the Gulf.

Kleberg teamed up with the film’s director, Ben Masters, after the two found they both had completed ambitious transcontinental treks: Kleberg had ridden a mountain bike from Mexico to Canada while Masters had made a similar journey on horseback with a pack of mustangs for an earlier documentary.

Their goal was to document the landscape along the Rio Grande before the potential construction of a border wall along the U.S.-Mexican border. Kleberg was both a character and associate producer of the documentary capturing the adventure called The River and the Wall. The film had its world premiere in mid-March at the South by Southwest Film Festival in Austin. It rolled out nationally in early May, with screenings in more than 200 locations and streaming on iTunes.

Kleberg says he hopes the adventure angle of the film will draw in a diverse audience.

“We’re hoping to interest people who may not otherwise watch a film about the Texas-Mexico border,” he says. “I don’t think the people in Texas or anywhere else in the United States know how beautiful and diverse this area is and that it changes every mile of border between Texas and Mexico. If they knew that they would be separated from it, that wildlife depend on it, how much all of that would be permanently altered, I think Texans would fight tooth and nail to figure out other solutions. It was a way for us to capture this super amazing landscape that is under-appreciated and hopefully capture its beauty in high-definition before it’s potentially altered.”

The documentary participants traveled about 20 miles each day, often camping along the river. Along the way, they interviewed people who could speak to the impact that a wall would have on issues of wildlife conservation, water access, cross-border culture, and property rights, including border patrol agents, farmers whose land would be split up, Mexican business owners, and politicians such as Republican U.S. Rep. Will Hurd and then-Democratic U.S. Rep. Beto O’Rourke.

“Texans love this river even though we may have forgotten about it, but it’s in our lore,” Kleberg says. “Every river has a story — the Brazos, the Colorado, the Guadalupe. I think the Rio Grande itself and the landscapes through which we go are characters that most Texans can identify with.”

“Hopefully our film provides a lens through which we as Texans and Americans can have this conversation,” he says. “Some things aren’t easy to understand in a soundbite, and the only way that we could think of to articulate the complexity of this multifaceted subject was to sit somebody down for 90 minutes and have them both see and hear from the border.”

Kleberg and his family live in the Travis Heights neighborhood of Austin. They can get into nature with a nearby walk along the creek, the lake, or at a park. “I try to connect to it as often as I can,” he says. “Our kids are bombarded with stimulus all the time and all day. Creating some space for them to free their mind, be kids, and be creative is so important. I can see it when I get them out even in these little parks. They immediately start creating and playing other things.”

He also makes every opportunity to take them to his family’s ranch and expose them to the kinds of experiences he had as a child. “I’m not necessarily spending the whole day telling them what we’re doing, and why we’re doing it. I just want them to be there.”

“For a long time, I ran away from it,” Kleberg says. “Not the responsibility necessarily. I just didn’t want it to define me. There’s a tremendous amount of history and legacy there. It’s something that I’m certainly proud of. Now, the way I live my life is in some way trying to honor that rather than feel a burden. I think most people perform better when they feel motivated to do so, not a responsibility to do so.”

One way that Kleberg is honoring his legacy is his new venture, Explore Ranches, which offers travelers access to a network of private, historic ranches. “What we’re doing is elevating the ranch, not just the accommodations, but the whole ranch experience with the guide, meals, and all of that,” he says of the company, which he co-founded in December 2018. “In some cases, bringing in a scientist to talk about it, archeologists, or with programming.”

The venture offers an option for landowners who have difficulty earning money on their properties. “It’s a revenue stream that we hope will allow them to hold on to it for multiple generations,” he explains. At the same time, it keeps the land open and preserves wildlife habitat. “As you start chopping up land among different owners, it’s not very healthy for the air, water, and land quality,” Kleberg says.

Kleberg says he appreciates the legacy of the generations that came before him on his family’s ranch. It’s clearly offered him a unique perspective that guides his work today. “It gave me an appreciation for the responsibility that anyone who owns land, whether it’s the home and your yard or it’s a wildlife habitat. I view all of us as stakeholders, even folks who are living in Austin. You really do have to care about it for these places to continue to remain wild.”

This article appeared in the spring 2019 issue of McCombs magazine. Click on the link to see the full issue.