When the Glass Ceiling Shatters

Companies with women in top leadership see improvements in the bottom line.

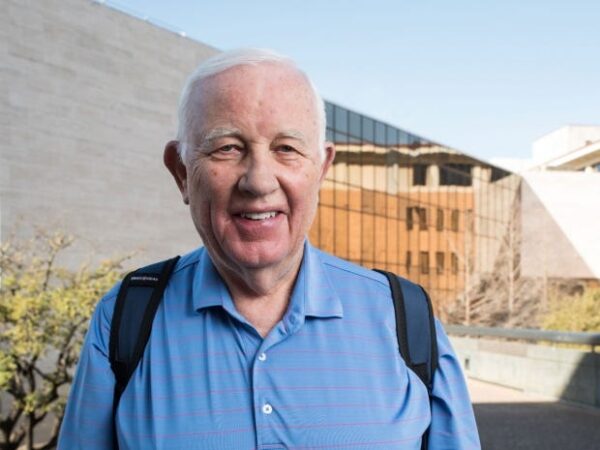

By Steve Brooks

Stephanie Paine, BBA ’03, could see that employees were burning out. Turnover was 60 percent at Healthbox, the firm where she’s chief financial officer. The reason, in her eyes, was a top management style that pushed employees for results without considering their human needs.

When a new president came on board, Paine saw an opportunity to “launch a culture crusade.” Together, they huddled with the entire staff to talk about what made workers happy and unhappy. They acknowledged extra achievement. They had check-ins every three weeks. Eight months later, not a single employee had left.

“Disrupting certain elements of an organization’s culture is important. I bring a fresh set of eyes to every process. It’s what I do.” — Stephanie Paine

Challenging Ingrained Ways

According to two new studies from the McCombs School of Business, she’s not alone. Women in boardrooms and C-suites bring new perspectives and challenge ingrained ways of doing things. These are some of the reasons that their influence ultimately improves the bottom line:

- Firms appointing women to top management teams improved their long-term financial performance, according to a study by Management Professor David Harrison and doctoral student Seung-Hwan Jeong.

“From the data we’ve seen, firms do as well, and usually better, if they shatter the glass ceiling.” — David Harrison

- To boards of directors, women bring an average of nearly 10 percent additional distinct areas of expertise compared to male directors, find Associate Dean for Research Laura Starks and Daehyun Kim, Ph.D. ’16. “We show that women who are newly added or are already serving on boards bring unique skills to these boards,” says Starks.

Benefits for Boards

The upper echelons of the business world are still overwhelmingly male. Though women account for 47 percent of the workforce, they make up only 15 percent of directors at publicly traded U.S. companies.

That prompted Starks and Kim, an assistant professor of accounting at the University of Toronto, to wonder whether boards were missing out. Earlier theoretical research showed that boards are more effective as corporate advisors when they contain a diversity of expertise. Female directors, they suspected, might also enhance boards by adding different and currently missing skills.

“The ‘old boys’ club’ in the minds of directors puts a limit on skill sets. The push towards more diverse directors might result in their being better endowed with information.” — Daehyun Kim

The researchers looked at boards in the S&P SmallCap 600, an index of companies with market capitalizations between $400 million and $1.8 billion, which average even fewer female directors than larger firms. Thanks to a recent securities rule that requires companies to list directors’ skills or qualifications, Starks and Kim could rank each director in 16 areas of expertise.

Not only did they find that new female directors offered more identifiable skills than male directors, but women also contributed skills that boards had been lacking. Of 519 new directors appointed between 2011 and 2013, the research showed that the average woman brought 66 percent more areas of expertise than her male counterparts.

While men were heavier on traditional business abilities like finance and operations, women added talent in such areas as risk management, human resources, and sustainability. Today’s boards are hungry for these skills, notes Starks: “There’s much more emphasis today on environmental and social issues by corporations than there was even five years ago.”

Women In the C-Suite

Harrison and Jeong, meanwhile, looked at how women operate in C-level roles. It’s the tier at which women are rarest, as they made up only 3.2 percent of CEOs appointed in 2013 and 2014 in Fortune 500 firms.

Three decades of studies have reached ambiguous and sometimes conflicting conclusions about whether women in high positions help or hurt a company’s performance. To resolve those differences, the researchers analyzed 146 previous papers, teasing out factors that might have influenced their outcomes.

A major factor, they found, was that CEOs have more managerial discretion in some firms — depending on the ownership and size of their company and the country in which it operates. Once they adjusted for those differences, they found that over time, firms with female managers did slightly better than average financially.

Though the advantage was in the range of 1 or 2 percent, those aren’t trivial numbers for large corporations. “You’re talking tens or hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue or return on assets,” says Jeong.

In the short term, though, incoming female leadership had the opposite effect. Stock returns did take small but detectable hits just after announcements of women CEOs, but that’s likely due to simple skittishness, not chauvinism.

“Women CEOs are rare. Almost anything rare is seen as risky and brings a sense of uncertainty. The market hates uncertainty.” — David Harrison

But the qualms of short-term investors could create opportunities for those who are more farsighted: long-term returns were more positive for women-led firms, as were accounting metrics such as return on assets. “I might want to buy just a bit after the announcement of a female CEO, because other folks are selling,” says Harrison. “I can scoop up some stock and, later on, I can watch it rise.”

Smarter Risk-Taking

Why does management benefit from including more women? For both studies, a key answer is what Harrison calls “a different set of eyes.”

Data suggest that women’s perspectives tend to challenge unspoken assumptions within groups dominated by men and lead to better decisions, Harrison explains. “The presence of women on top management teams helps those teams process information in a more comprehensive way,” he says.

That’s a role that travel technology advisor Ellen Keszler, MBA ’87, has played on more than one board. “They were early-stage companies, and once they’d gotten to a certain point, I suggested it was time to put in a more formalized bonus and incentive compensation program,” she says. “They were finance-focused, where I had more of a human relations perspective. I was saying, ‘Let’s think about employees. Is their compensation motivating them?’”

Sue Gove, BBA ’78, agrees. “I see women pushing for more accountability, challenging the way things are done,” she says. Gove is president of Excelsior Advisors and is an independent director for companies like AutoZone and Logitech.

Harrison and Jeong also found that women have lower appetites than men for some kinds of strategic risks. In the studies they reviewed, firms with women in top jobs scored lower on risky measures like financial leverage, capital expenditures, and share price volatility. “Having a woman on a team helps to promote smarter risk-taking,” says Jeong.

Paine, the Healthbox CFO, used to work in private equity acquisition. She sized up the risks when assessing their value. “I tended to view sky-high valuations with a skeptical eye,” she says. “I was the one asking, ‘Is the company at too early of a stage? Is there too little revenue? Is the market really going to support it?’

“It’s not just wanting to jump on the bandwagon of something management recommends, but saying, ‘Let’s be more thorough with our analysis and evaluation.’”

—Stephanie Paine

Women also can bring novel ideas to a board that is stuck in a rut, says Kim. “Expertise is an important source of professional opinions. Bringing in diversity of expertise is really bringing in diversity of opinions.”

But Gove cautions that diversity on boards doesn’t come about on its own. She’s used to being a company’s first woman director and pushing her colleagues to add more.

“The pool is still tilted towards men, for sure,” says Gove. “The best approach a board’s nominating committee can use is to set out in its criteria that it wants to fill an open seat with a female candidate.” The approach works, she adds. “Each of my boards today has at least two female directors.”

From the spring 2017 issue of McCOMBS, the magazine for alumni and friends of the McCombs School of Business.